Religion in Egypt

Religion plays a significant role in various facets of social life in Egypt and is supported by legal frameworks. The predominant faith in the country is Islam. However, due to the lack of official statistics, estimates regarding religious demographics can vary widely. Following the 2006 census, subsequent figures have been derived from assessments conducted by religious organizations and non-governmental entities. The majority of the population identifies as Sunni Muslim, with estimates fluctuating between approximately 80% and 94%. The next largest religious community consists of Coptic Christians, whose numbers are estimated to range from 6% to 20%. The accuracy of these figures is often debated, as many Christians claim they have been systematically underrepresented in the available census data.

Egypt is home to two prominent religious institutions. The Coptic Orthodox Church, established in Alexandria by St. Mark in the mid-first century, holds significant historical importance. Additionally, the Al-Azhar Mosque, founded in 970 A.D. by the Fatimids, is recognized as the first Islamic university in the country.

The Coptic minority in Egypt, which is rooted in one of the country's oldest religious traditions, has emerged as the largest ethnic and religious minority following the Islamic conquest. This community has increasingly encountered legislation that may lead to discrimination against them. The marginalization of Copts intensified after the 1952 coup orchestrated by Gamal Abdel Nasser. Historically, Christians were required to secure presidential consent for even minor modifications to church structures. However, in 2005, the law was amended to delegate this authority to local rulers, resulting in fewer barriers for Copts in the construction of new churches.

The religion of ancient Egypt, characterized by its intricate beliefs and rituals, played a crucial role in the fabric of ancient Egyptian society. The Egyptians engaged in prayers and offerings to numerous deities, whom they believed governed the world, in hopes of securing their favor. A significant aspect of this religious framework was the role of the pharaohs, who were regarded as divine rulers endowed with sacred authority. They served as intermediaries between the populace and the gods, tasked with upholding the ancient deities through various rituals and ceremonies, thereby safeguarding their own power and status. The state allocated substantial resources to religious observances and the construction of temples dedicated to the pharaonic gods.

Individuals also had the opportunity to connect with the deities for personal reasons, seeking assistance through prayer or invoking magical practices. While these personal interactions were separate from formal rituals and institutions, they were nonetheless closely intertwined. Over time, as the authority of the pharaoh diminished, the prominence of these religious traditions grew. The Egyptians' belief in an afterlife and the significance of funerary customs is reflected in the extensive measures taken to ensure the continuation of life after death, including the provision of elaborate graves, valuable goods, and offerings intended to preserve the bodies and souls of the deceased along with their possessions.

In Egypt, Muslims and Christians share a rich history characterized by common national identity, ethnicity, societal norms, cultural practices, and language.

A notable aspect of religious coexistence in Egypt is the proximity of mosques and churches. In 2002, during the Mubarak administration, January 7 was officially designated as a holiday to celebrate Christmas. However, it is important to note that Christians constitute a minority in law enforcement, state security, and public service roles, often facing discrimination in the workforce due to their religious beliefs.

The evolution of religious beliefs over time reflects a rich history that traces back to prehistoric Egypt, spanning more than 3,000 years. Throughout this extensive period, the significance of various deities fluctuated, with their intricate relationships undergoing transformations. Consequently, certain gods gained prominence over others, notably the sun god Ra, the creator god Amun, and the mother goddess Isis. A notable shift occurred during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten, who established his capital at Tel El Amarna in present-day El Minya, where he introduced the worship of a singular deity, Aten, thereby supplanting the traditional pantheon. The legacy of ancient Egyptian religion is evident in the numerous writings and monuments it produced, which have profoundly influenced both ancient and contemporary cultures.

The ancient Egyptians perceived the natural world around them as imbued with divine forces, which they believed inhabited the fundamental elements of the cosmos, including the earth, sky, ether, the Nile's inundation, as well as the sun and moon. These forces manifested in human forms, leading to the emergence of numerous cosmic deities of universal significance. Over time, these deities transcended their regional or city-specific origins, as their presence was felt throughout the land, diminishing the necessity for a structured belief system or dedicated local temples. The poetic imagination of the Eastern peoples contributed to the anthropomorphization of these divine ideals, as they were articulated in the language of human experience. While only a few of these myths have survived in complete form from relatively later periods, numerous references to mythical events in ancient texts suggest that these narratives were already flourishing by the end of the Fifth Dynasty at the very least.

In the ancient state, the Egyptians characterized God as a figure of stability and assurance, radiating like the sun. Their perception of the divine was that of a brilliant and majestic presence, embodying kindness. The gods were believed to be the creators of life, nurturing and protecting the child with love, guidance, and sustenance. They were seen as guardians throughout one's life, providing virtue, health, and clothing, ultimately shaping the entirety of one's existence under divine influence.

The ancient Egyptians held a belief that humanity serves a Lord who is devoted in worship and love. While many of the attributes mentioned are often associated with the deity Ptah, this is coincidental, as numerous names from the ancient state are linked to relics predominantly discovered in the Memphis region. It is expected that the prevalence of other divine names arises from the attributes associated with them, which often relate back to the name Ptah, as well as to other deities, reflecting a broader connection among the divine entities.

The ancient Egyptian belief system suggests that the fates of individuals are not entirely predetermined and can be altered through one's actions, provided that it aligns with divine will. As long as the future remains under divine control, a child is born under the watchful care of the gods, with parents strengthening their connections to the divine to facilitate this blessing. From that moment, an individual’s actions are contingent upon the approval of the gods. While humans may propose various actions, it is ultimately God who determines their outcomes, as articulated by an Egyptian sage: "A person may voice intentions, but the ultimate decision rests with the Lord." The purpose of the funeral rites was to liberate the soul from the physical form, allowing it to roam freely and eventually reunite with the body for eternal life. Additionally, the preservation of the corpse was deemed crucial, as it was believed that the deceased would return to their body each night to rejuvenate before departing again at dawn.

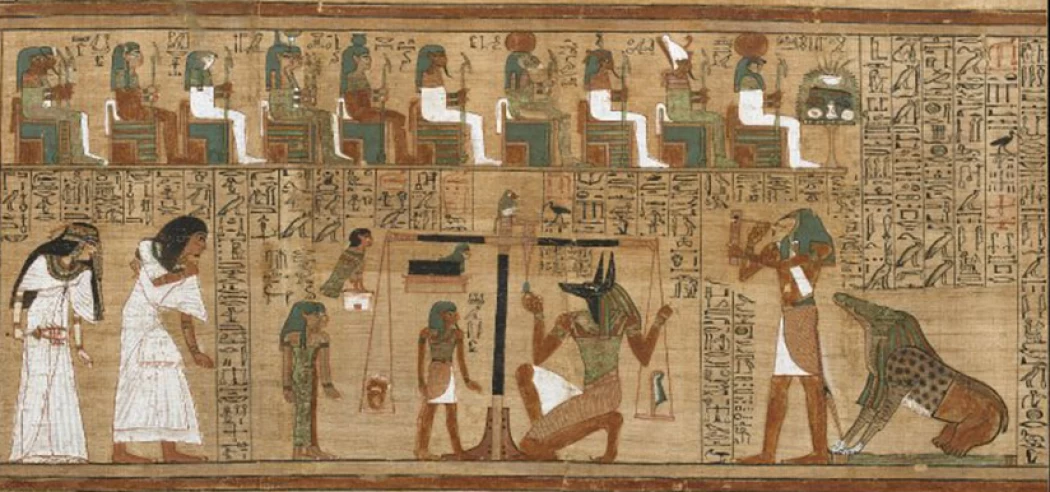

In the earliest periods, it was thought that the deceased pharaoh would ascend to the heavens and reside among the stars. However, during the Old Kingdom (circa 2686–2181 BC), this belief evolved, and the pharaoh became increasingly associated with the daily resurrection of the sun god Ra and the ruler of the underworld, Osiris, as these deities gained prominence. In the well-established afterlife beliefs of the New Kingdom, the soul was required to navigate various supernatural threats within the Duat before facing a final judgment known as the "Weighing of the Heart." This judgment was conducted by Osiris along with the Assessors of Maat. During this process, the gods evaluated the actions of the deceased during their lifetime, represented by the heart, against the principles of Maat to ascertain whether the individual had lived in accordance with these principles. If deemed worthy, the ka and ba of the deceased would merge to form an Akh. There were multiple beliefs regarding the destination of the Akh, with many asserting that the deceased resided in Osiris's domain, a verdant and idyllic region of the underworld. The solar conception of the afterlife, wherein the soul accompanied Ra on his daily journey, was primarily linked to royalty but was also believed to extend to others. Throughout the Middle and New Kingdoms, the idea that the Akh could traverse the realm of the living and exert a certain magical influence on events there gained increasing acceptance.

If Egypt has often been referenced by historians as ‘the Cradle of Civilization’, it has probably one of the most complicated religious aspects in entire human history. The fertile banks of the Nile did host agriculture, but they also produced a vast culture, where religion permeated every single aspect of everyday life, politics, and social order. From the earliest days of ancient Egyptian civilization up to this day, despite being primarily a desert dry land, Egypt has been a melting pot of different religions, starting from polygamy to finally embracing monotheism.

In this piece, Section II, How We Were: Reflections on Egyptian History, From Ancient Polytheism to Christianity & Islam, will be reviewed and analyzed, as well as the role of religion in the lives of the Egyptian population.

As a society, it can be said that religion was the foundation of ancient Egypt. The ancient Egyptians worshiped as they knew that everything from the annual flooding of the Nile to the cycle of life and death was not only natural but controlled by some divine power. This was a belief characterized by a multiplicity of deities, all of whom were in charge of a specific facet of existence and/or nature.

The Major Gods and Goddesses

Ra (or Re): Revered as the God of the Sun, Ra has been depicted as the most potent deity in ancient Egyptian religion. It was believed that Ra inhabited the sky during the day, providing light to the earth, and resided in the underworld at night. He would oftentimes be portrayed with a falcon’s head and wear a sun disk on top of his head.

Osiris: Osiris was an Egyptian death and resurrection god and held a significant place in Egyptian mythology in representing the concept of life as a cycle of birth, death, and resurrection. The Osiris myth and his resurrection, in the capable hands of Isis, his wife, became the pillars of the Egyptian afterlife experience.

The goddess was immensely popular and powerful. She was a protector of motherhood, magic, and fertility. Her protective aspect and the ability to bring Osiris back to life made her worshiped.

Horus, the god of the sky and of the king, is often shown as a hawk. He was also known because of his rivalry with the chaos god Set for dominion over the land of Egypt, which represents the struggle of order and chaos.

Anubis is the Egyptian god associated with funerary rites and the protection of the dead. He had the important task of supervising the ceremony of the heart's weighing, which assessed a person’s spirit in the next world.

The gods were not distant or abstract figures; they were present in every facet of life. Egyptians built temples across the country, conducted elaborate rituals, and offered daily prayers and sacrifices to ensure the favor of the gods and maintain ma’at—harmony and order.

Worship wasn’t the only reason for building temples; these structures were believed to be the earthly homes of the gods. The pharaohs had enormous temples like Karnak and Luxor built to worship and carry out rituals for the gods as well as to showcase the power of their rule over the land. No one was permitted to enter the temple’s most sacred, innermost areas except for the priests, who were thought to be the only ones capable of interacting with the gods.

Priests offered meals, incense, and prayers to the gods on a daily basis, performing their duties towards ensuring the gods’ continuous provision of security over the land of Egypt. These clergymen were very powerful and at times even had political authority as they helped the pharaohs in religious affairs.

For the Ancients, death was not a permanent end; there would be life after death. This notion fueled the people’s efforts to focus on death and think about how they would prepare in the appropriate way for their journey to the underworld, which in their minds was not an easy place to reach but one that guaranteed everlasting bliss as long as the challenges were overcome.

Mummification and the Preservation of the Body

Mummification was pivotal in shaping the Egyptian view of what happens when one dies. The body was to be maintained so that the ‘ka’ (or soul) would remember and go back to its residence after death. Mummification came to be practiced with a set of procedures that included arts of organ procurement, chemical treatment, and linen envelopment of the entire body.

A process of putting up preparatory arrangements for one’s afterlife would also include making tombs, which would have items that the dead person would require, such as food, clothes, and upright ‘ushabti’ figures meant to depict servants. The magnificence that royal burial places such as the Giza pyramids and those in the Valley of the Kings display indicates the extreme measures taken to ensure adequate rest and healthcare for the leaders when they die.

The mummification custom was bound to the Egyptian people's love of the afterlife. Bodies had to be maintained in a way that allowed the spirit, or 'ka', to identify it and be able to go back in after death. Mummification came to be seen with specific practices, which included the arts of organ downsizing, substance drying, and body plastering with bandages.

Another aspect of preparing for eternity was that of constructing tombs containing the essentials for the deceased, such as an abundance of food and clothes and miniature statues of servants known as ushabtis. Such an adulation can be seen from the wonderful construction of royal burial sites such as those surrounding the Great Pyramids of Giza and along the Valley of the Kings, where endless hope lies for the reasonable resting of the leaders within the period of their deaths.

The “weighing of the heart” ritual is one of the key convictions regarding the hereafter. In Egyptian cosmology, when a deceased individual was brought to the land of the dead, the god Anubis was tasked with weighing the heart against the feather of Ma’at, the deity representing truth and justice. Where the scales tipped in favor of the feather, the individual was considered fit to take his place among the dead in the other world. If the heart tipped the scale against the feather, then due to some impertinent act or lie, that heart would be consumed by the ferocious goddess Amit and the essence would no longer exist.

3. The Introduction of Monotheism: The Amarna Period

Throughout the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten, also known as Amenhotep IV, which was between the years 1353 and 1336 BCE, many changes were witnessed, especially in Egyptian religious practices. Akhenaten believed there was only one God to worship, and that was Aten, the sun disk, and he promoted the worship of Aten only. He constructed a new city called Akhetaten (Amarna, modern) and concentrated on the worship of this one god, excluding completely the rest of the traditional deities in the Egyptian pantheon.

The extent of how long this extreme change in religious practices lasted is very minimal. After the death of Akhenaten, the former worship of many gods was reinstated by the administrations that followed him, particularly through King Tutankhamun, and the cult of Aten was, for the most part, expunged from history. Still, the issue of Akhenaten's obsessive tendencies concerning religion remains a curious page in the story of religions in ancient Egypt. It demonstrates how potential changes in religion can be such a threat even when a rigid system is in place.