The Temple of Beit el-Wali: A Monument of Power and Faith

The Temple of Beit el-Wali: A Monument of Power and Faith

Nestled in the region of Nubia, the Temple of Beit el-Wali is an awe-inspiring example of ancient Egyptian architecture. Carved directly into the rock, this small but historically significant temple was built during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II. Dedicated to the gods Amun-Re, Re-Horakhti, Khnum, and Anuket, Beit el-Wali was the first of a series of temples Ramesses II constructed in Nubia, emphasizing both his devotion to the gods and his control over the region.

The temple’s name, “Beit el-Wali,” which translates to “House of the Holy Man,” suggests it may have been used by a Christian hermit at some point, though its origins lie in Egypt’s New Kingdom. Like many other monuments in Nubia, it had to be relocated in the 1960s due to the construction of the Aswan High Dam, which threatened to submerge it. Through the combined efforts of Polish archaeologists, and funding from Swiss and American institutes, Beit el-Wali, along with the Temple of Kalabsha, was successfully moved to higher ground, preserving its legacy for future generations.

A Symbol of Egyptian Control in Nubia

The construction of Beit el-Wali was part of a larger Egyptian policy of maintaining control over Nubia, a region known for its rich resources. Temples such as this one served not only religious purposes but also functioned as tools of political influence. They were used to impress upon the local population the power of the Egyptian state and the divine right of Pharaoh to rule over them.

During the New Kingdom, Egypt's influence over Nubia extended beyond military conquest. Egyptian officials governed the land, and Nubian elites were systematically acculturated. Many were sent to Egypt, where they adopted Egyptian customs, language, and religious practices, eventually taking on Egyptian names. The artwork and inscriptions in the temple reflect this process, often showcasing Ramesses II’s military victories and tributes brought by the Nubians as symbols of submission.

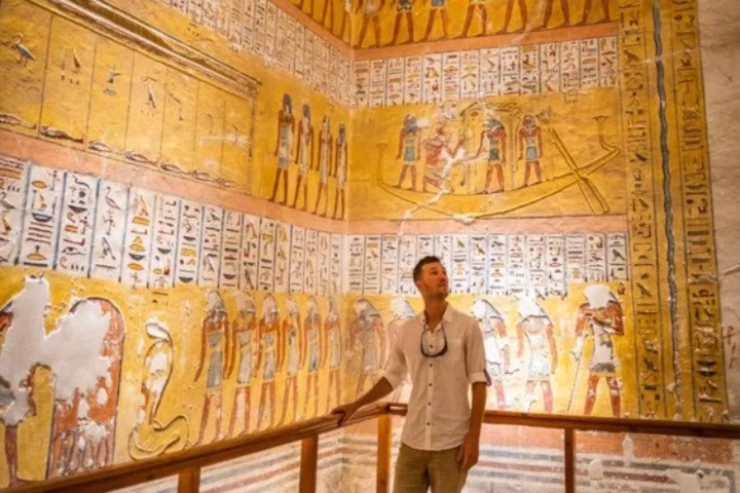

Artistic Splendor Amidst the Rock

Despite the temple’s relatively small size, it features impressive reliefs that offer a glimpse into Egypt’s imperial grandeur. One of the most captivating scenes depicts Ramesses II in battle against the Nubians, charging forward with his two sons, Amun-her-khepsef and Khaemwaset, by his side. Another relief shows the Pharaoh seated on his throne, receiving tributes of exotic goods from Nubia, such as leopard skins, giraffes, monkeys, ivory, and gold. These offerings highlight the wealth and diversity of the Nubian land, as well as Egypt’s dominance over it.

The temple’s interior is adorned with scenes of Ramesses II triumphing over his enemies, a recurring theme in ancient Egyptian art. In one powerful image, the Pharaoh is shown trampling his foes, grasping their hair with one hand while striking them with the other. These visuals reinforce the image of Ramesses as both a mighty warrior and a just ruler, devoted to maintaining Egypt’s supremacy.

Religious Significance and Unique Design

Beyond the depictions of military might, Beit el-Wali also reveals Ramesses II’s devotion to the gods. The temple’s sanctuary is home to statues of the Pharaoh alongside important deities such as Isis, Horus, Khnum, and Anuket. In one particularly intimate scene, Ramesses is shown as a child being nursed by both Isis and Anuket, symbolizing his divine connection and right to rule.

Architecturally, Beit el-Wali stands out from other temples of the era due to its rock-cut design. The temple is composed of a forecourt, an anteroom supported by two columns, and a sanctuary hewn into the surrounding rock. While small in size, its plan and artistry set it apart from Ramesses’ later constructions further south.

A Christian Past

In the early Christian period, Beit el-Wali was repurposed as a church. This new chapter in its history underscores the continuity of sacred spaces in Egypt, as ancient temples were often adapted for Christian worship. The temple’s remarkable artistic and architectural details were first thoroughly documented in 1938 by Günther Roeder, helping to cement its place in Egypt’s rich archaeological heritage.

Today, Beit el-Wali remains a testament to the skill and ambition of Ramesses II, a ruler who left an indelible mark on both Egypt and Nubia. Its walls continue to tell the story of Egypt’s imperial might, its relationship with the Nubian lands, and the enduring power of faith.