Wadi El-Natrun in Egypt

Details about Wadi El-Natrun in Egypt

During the Pharaonic era, this area was considered sacred because of the presence of sodium salt composed of carbonate, bicarbonate, sodium sulphate and chlorine, which was the salt used for the purification of mummies. From the first centuries of the Christian era, this region became an important place of churches and monasteries whose founder was Saint Markus the great who lived there in 330.

Travelers looking for peace and stunning scenery can find a hidden gem that provides a unique experience deep within the Egyptian desert, far from the bustle of large towns. Greetings from Wadi El Natron, a magical valley that promises to charm you and provide a once-in-a-lifetime experience. This post will discuss the wonders of Wadi El Natron and show you why it should be a top priority on your vacation schedule.

The name "Wadi El-Natrun" means "Valley of the Natrun" in reference to mineral salts found in the area, including natron, a mineral salt used in embalming and body preservation practices in ancient Egypt. The old natron quarries were exploited for various uses, including the manufacture of cosmetics and medicinal products. These monasteries played a crucial role in the development of Coptic Christianity and served as centres for teaching and preserving religious traditions. They are also places of pilgrimage for Coptic Christians from around the world.

Another popular spot for bird viewing is Wadi Naturn. It has nine minor lakes spread out along its main axis, with a combined size of about 200 km . Typha wetlands are found when there is an abundant supply of freshwater, usually along lakeshores. The moist salt marshes on the flooded eastern coast are dominated by Juncus and Cyperus.

The Wadi's history and significance to Coptic Christians go all the way back to the fourth century AD. When monastery life had not yet evolved, Christianity first made its way to the region through St. Macarius the Great, who withdrew there in c. 330. Holy men lived as hermits outside of society at this time. But St. Macarius's fame quickly drew admirers, who erected cells close by and so established a loose union of monastic communities. In neighboring regions like Nitria, many of these early inhabitants had already adopted a Christian hermit lifestyle. As a result, Scetis served as a center of consolidation rather than innovation.

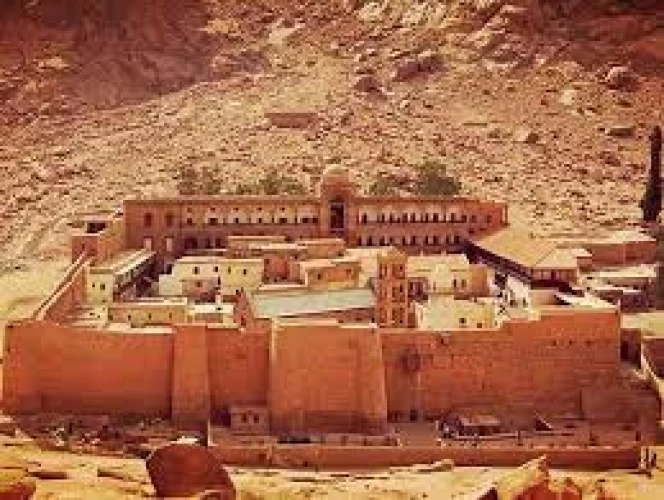

The informal grouping of Christian settlers had become four monastic communities by the end of the fourth century AD. These were the monasteries of John Kolobos (also known as John the Little), Bishoi, Macarius, and Baramus (the ancient). Like Nitria and Kellia, Scetis was occasionally the target of raids by nomadic desert dwellers, so at first these monasteries were just groups of individual cells and dwellings centered around particular churches and communal facilities. However, over time, they evolved into enclosures with walls and watchtowers for protection.

The monasteries of Wadi al-Naturn were looted and destroyed in 407, 434, and 444 by the nomads of the Libyan desert. Raids toward the end of the sixth century did, in fact, nearly wipe out the local population. Thus, the monks constructed towers for their residences and walls to secure their monasteries in the ninth century, perhaps in response to another siege in or around 817. In the years that followed, the monks started to move from their dispersed cells into the fortified monasteries. Initially, many of them lived outside the walls of the walled monasteries, only withdrawing to them in times of need. As the monks congregated behind the enclosure walls for security, monastic life seemed to be becoming increasingly cenobitic by the fourteenth century. When the plague wiped out a large portion of the monastic community throughout the middle times, walls did not help.

Wadi al-Natrun is one of the cities of Beheira Governorate, located on the northeastern outskirts of the Egyptian Western Desert, about halfway between the desert road linking Cairo and Alexandria, and facing the city of Sadat.

Wadi El-Natrun is not a valley in the well-known sense, but it is low in the Western Desert. Wadi El-Natrun borders to the north the Abu al-Matamir Center and the Badr Center, and to the east is the city of Sadat, while the center of al-Hammam is located in the Matruh Governorate, west of this depression, and finally to the south of it is the city of the Sixth of October.

This area called Wadi Al-Natroun was of great importance during the era of the Pharaohs, as the salt was extracted from this land and called the salt of the Natron known scientifically as sodium bicarbonate. Hooker, salt field, and other such names.

He also obtained a high holy reputation in Christianity, as a result of the passage of the Holy Family through him to escape from King Herod until he reached the first monastic congregation in it in the fourth century AD, at the hands of the great headquarters that established the monastery of Anba Makar and then followed by three other monasteries, namely the Monastery of Anba Bishoy and the Monastery of El-Baramos and the Monastery of Syrian, until the number of monasteries reached 700 monasteries in the valley until they started shrinking to now only four monasteries, while the rest were lost, so the valley is considered one of the most important sacred areas for followers of the Egypt Coptic Orthodox Church.

Tourism in Wadi El-Natrun is concentrated in many Coptic monuments, where monasticism began in small villages engraved in the hills, then natural conditions were imposed on the hermits to set up converging complexes, and from here began the idea of gathering inside monasteries to protect from barbaric raids, as internal fortresses were established in each monastery and they are still A list exists so far, and a large number of Christians have taken refuge in it to escape the grievances of the Romans. After the Islamic conquest of Egypt, monks and Natron came to the Arab leader, Amr ibn al-Aas, so he insured them on their lives and the freedom of their worship and took it upon himself to provide them with what they needed.

Lake Hamra or Ayoub's well as its people call it attracts visitors for medical tourism because it is distinguished by its high salinity and its healing properties specifically for patients with skin diseases..and this lake is located in the middle of the desert road linking the cities of Alexandria and Cairo in the Wadi Natrun region.

The arid desert embraces that lake, which is characterized by extreme salinity. In the middle of this lake, an eye bursts out from which a source of the sweetest and most healthy food with a miraculous ability to heal skin diseases explodes. As a result of the flow of this sweet water on this extremely salty spot, a brilliant colored gradient plate is formed, announcing the power of the Creator.

The most significant monasteries in the region of Wadi El Natrun:

- Monastery of Anba Bishoy:

The Monastery of Anba Bishoy is the largest of the monasteries in Wadi El Natrun. This monastery is named after Anba Bishoy, a disciple of Anba Macarius.

-Monastery of Baramous:

The name of Baramous Monastery goes back to Saints Maximus and Domatius of Rome, two Roman fathers of the fourth century AD.

-Monastery of Abu Macarius

-Monastery of the Virgin Mary of the Syrians

The Monastery of the Virgin Mary of the Syrians is one of the four monasteries remaining in Wadi El Natrun in the Western Desert of Egypt, and it is also the smallest.

This monastery was found in the sixth century AD and was first called “Our Lady of Anba Bishoy” as some monasteries with a double name had been established. The monks established a church next to each main monastery.