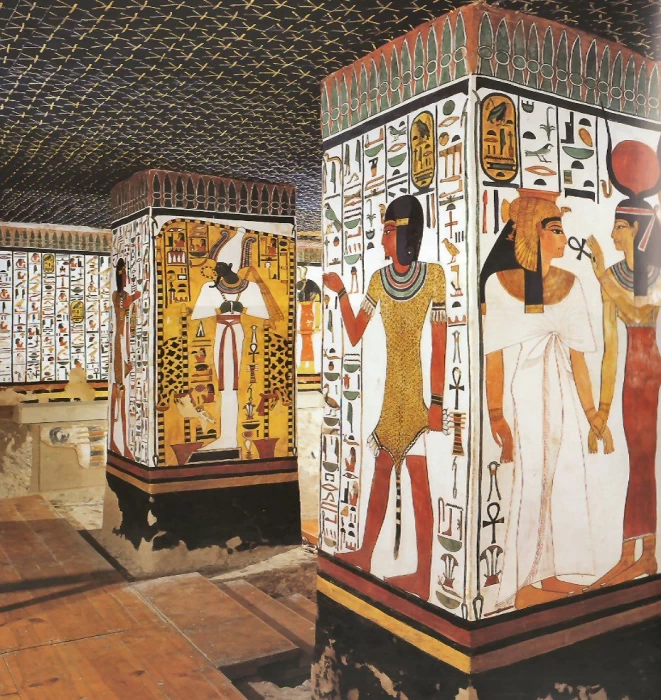

Tomb of Queen Nefertari

Tomb of Queen Nefertari

The history of ancient Egypt features a number of prominent female leaders. Some of them who actually acted like true, ruling “pharaohs” were Hatshepsut (c. 1479-c. 1457 BC) and Cleopatra VII (51-30 BC), both women who sat on the Egyptian throne for years. There were also the great queens of the New Kingdom (1550-1090 BC) Nefertiti, the wife of Akhenaten (1371-1355 BC), and Nefertari, one of the celebrated eight wives of Ramses II (c. 1279-c. 1213 BC). While Nefertiti is more popular for the exquisite portrait bust of her that is located in Berlin, Nefertari is famous mostly for her large burial site situated in the Valley of the Queens.

There's no question that Nefertari's tomb ranks the prettiest of all tombs in Egypt already built in terms of the scope and above all the artistry of the decoration. Indeed, none of the monumental tombs located in the Valley of the Kings can boast such a fully coherent pictorial representation. Though no one should expect to find any particular themes in the iconographic program that would stand out as particularly innovative. Expectedly, it narrates the tale of the dead person's soul interred in the ground and the journey she is expected to take through the afterworld ruled by Osiris.

Embarking on this odyssey, one can start at the ‘Hall of Gold’ that housed the queen’s sarcophagus. Here, the soul of the queen underwent gestation and finally reincarnation and as it made its way back to the ante-room, it reincarnated into the bright light before ‘coming out into the day’ like a sun that rises to mark the break of a new day. Conforming to the expected structures of an Egyptian tomb of the second millennium B.C. AD like most other tombs, what makes Nefertari’s tomb outstanding among others is the precision of the outlook with an overall use of flat vibrant colors that is effective.

When the Turinese Egyptologist Ernesto Schiaparelli entered the building in 1904, he found only scattered elements, oushebtis (funerary statuettes), a few jewels and fragments of furniture. The tomb had long since been looted. But the beauty of the wall paintings immediately aroused public enthusiasm and, for almost half a century, tourists flocked to visit the final resting place of “Ramses II's great love”. As at Lascaux, this parade of visitors upset the microclimate that had prevailed there for two millennia.

It was during the reign of Ramses I (c. 1295-c. 1294 BC) that queens began to benefit from fitted tombs (rather than simple shaft tombs), located within a specific necropolis. The Valley of the Queens was home to the graves of around a hundred royal wives, as well as princes and, perhaps, high-ranking private individuals. Many of these tombs were of mediocre workmanship or remained unfinished.

In this context, how can we explain the fact that the first wife of Ramses II was the beneficiary of such a high-quality funerary ensemble? The Pharaoh's love for his wife is a romantic explanation, but one that is difficult for historians to verify. While the inscriptions relating to Nefertari abound in amorous epithets - “sweet of love”, “beautiful of aspect”, “full of charms” - and lead us to believe that Ramses II was deeply in love with his wife, it should be pointed out that some of them come from the queen's tomb, where - and this is an essential fact - the sovereign appears nowhere!

Latest Articles

Admin

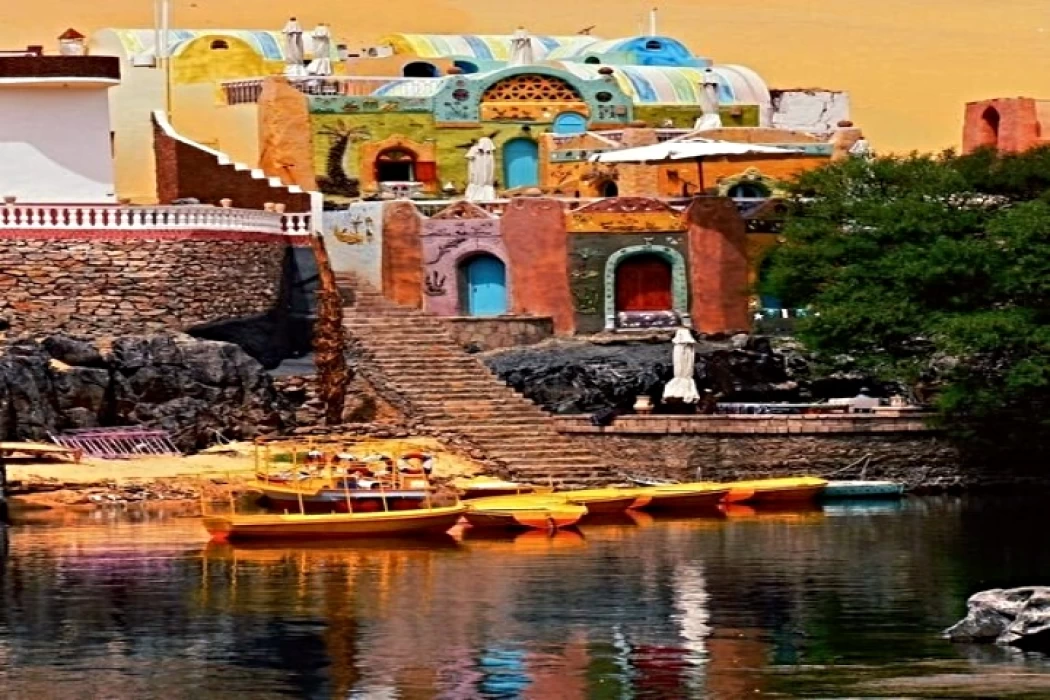

Aswan Governerate in Egypt

Aswan was known as ‘Sonu’ in ancient Egyptian times, meaning market, as it was a trading centre for caravans coming to and from Nubia. In the Ptolemaic era, it was called ‘Sin’ and the Nubians called it ‘Yaba Swan’. It was also known as the Land of Gold because it served as a great treasure or tomb for the kings of Nubia who lived there for thousands of years. Before the migration, Aswan's borders extended from Asna in the east to the border of Sudan in the south, and its inhabitants were Nubians, but after the Islamic conquest of Nubia, some Arab tribes settled there.

Admin

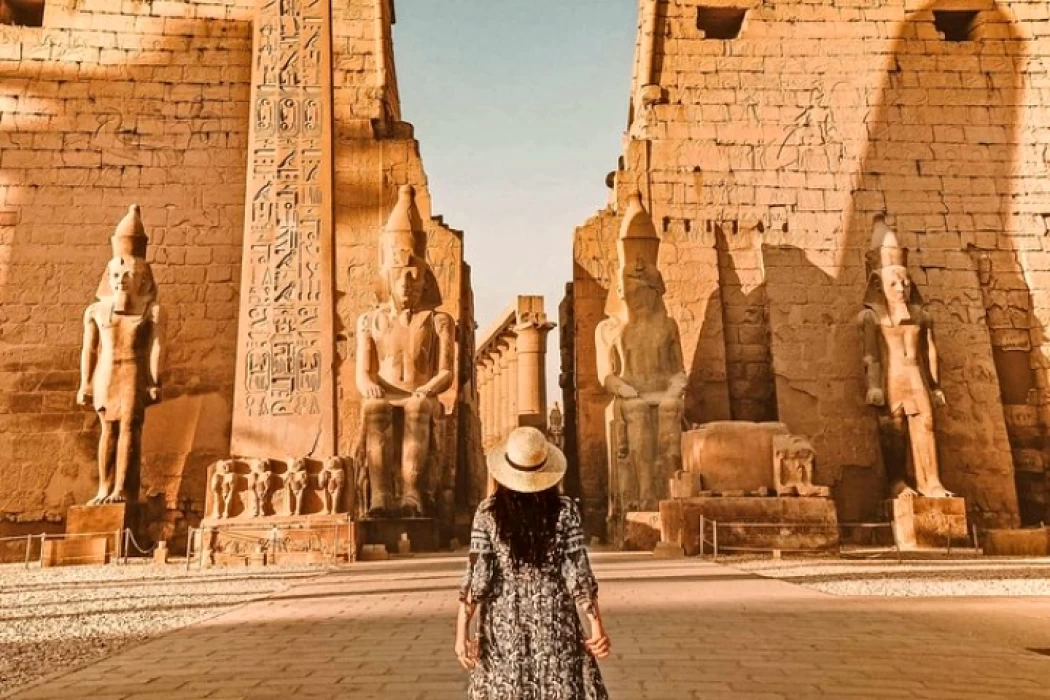

About Luxor Governorate in Egypt

The South Upper Egyptian area is home to the Egyptian governorate of Luxor. Its capital is Luxor, which was formerly Thebes, the capital of Egypt throughout multiple pharaonic eras. Its centers and cities are spread over both sides of the Nile River. The said governorate was established by Presidential Decree No. 378 of 2009, which was promulgated on the 9th of December of that year.

Admin

History of kafr El Sheikh Governorate

Kafr El Sheikh Governorate, located in the far north of Egypt in the Nile Delta, overlooking the Mediterranean Sea, is characterised by the diversity of natural life and environments, and is one of the Egyptian cities that can be visited after the end of the first semester exams at universities and schools, as it features many diverse tourist and recreational places at symbolic prices within everyone's reach.

Admin

Egypt's New Administrative Capital

The New Administrative Capital is considered the project of the era because it reflects a perfect image of the future and progress on the economic, cultural, social and civilisational level, as the capital is considered the new capital of Egypt at the present time. The importance of the New Capital is that it is a comprehensive transformation of the future of buildings, services and national and mega projects in Egypt.

Admin

Al Gharbia Governorate

The Governorate of Gharbia is inclusive in the geographical area of The Arab Republic of Egypt which is in the African continent, more specifically in the region surrounding the Nile delta, between Damietta and Rashid governance. To the control of the region from the north is Kafr El-Sheikh Governorate, from the south Menoufia Governorate, from the east – Dakahlia, Qalyubia Governorates, and to the west is the Beheira Governorate.

Admin

Hamata Islands (Qulaan Archipelago) in Marsa Alam

Each reserve has several sectors. In Wadi El Gemal Reserve, there is one of the natural areas called the Hamata area or Hamata sector in Wadi El Gemal Reserve. Its sectors are the perfect and most ecological, land and water, and host countless animals and plants found in the oceans and on the land.