King Shepseskaf | Last King of the Fourth Dynasty

Last King of the Fourth Dynasty

After the majority of his 4th Dynasty predecessors chose to construct their funerary monuments, Shepseskaf (2472–2467) was the first to return to Saqqara: Dahshur, in the south, for Snéfrou (2575–2551); Abou Rawash, also known as Abou Roach or Abu Roache, for Djédefrê (2528–2518); and Guizèh, in the north, for Khoufou (or Khéops, 2551–2528), Khafrê (or Khéphren, 2518-2492), and Menkaourê (or Mykérinos, 2492–2472).

The fact that Shepseskaf did not build his tomb in the same place as his predecessors is seen by some Egyptologists as a sign of a change in religion and belief. During his reign, the cult of Ra was called into question, and the king would have preferred not to build opposite Heliopolis.

Other specialists see it as a desire to distance himself from the policies of his ancestors. Some give evidence that the immense constructions of Khufu and Khafre had completely exhausted the royal family's wealth. This last argument, however, is contradicted by the fact that Shepseskaf completed the funerary temple of his father Menkaure, something he would not have done if money had been scarce.

Pending further discoveries, the debate remains open, as the motivation for this change may simply be a question of space. For the King chose a sector of Saqqara that does not appear to have been used before: Saqqarah South. In fact, his tomb is the southernmost royal tomb on the site.

In the same vein, Shepseskaf chose not to follow the standard construction plan established by his 4th Dynasty ancestors for his tomb. His tomb remains typical in design, both in the layout of the funerary apartments and in the materials used. It consists of a mastaba-like superstructure with a valley temple (or reception temple) and a 760 m ascending causeway, linking it to the funerary temple incorporated in the mastaba's enclosure wall.

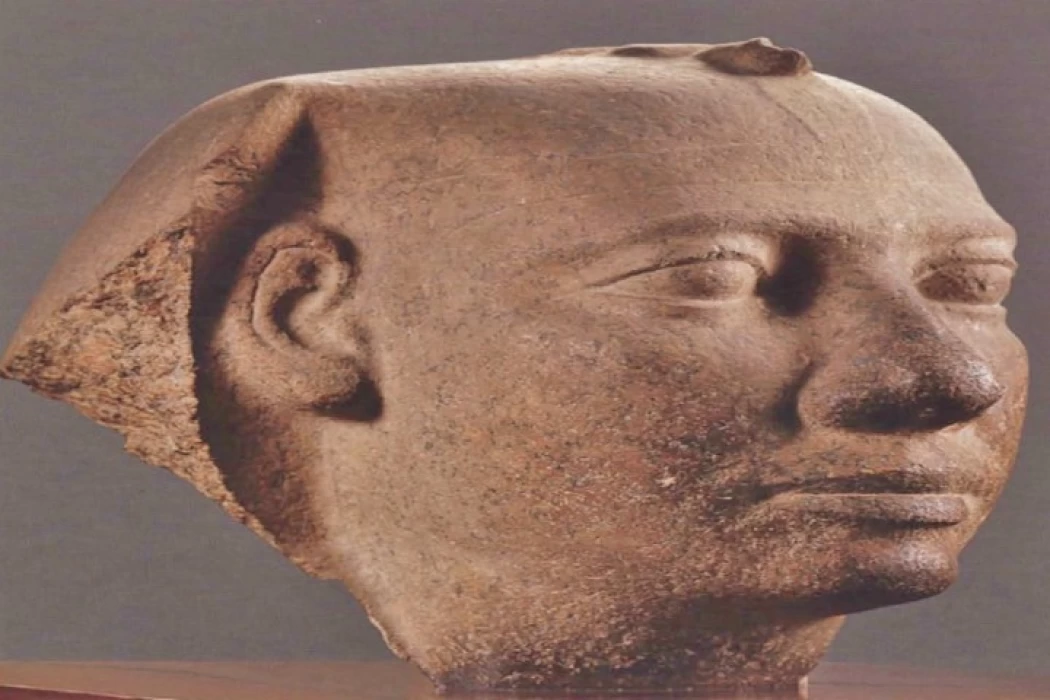

The satellite pyramid and the Queen's pyramid were certainly not built. The valley temple has yet to be precisely located and has not yet been excavated. The mastaba is in fact surrounded by two mud-brick walls some forty metres apart. The funerary complex was begun in stone, but finished in mudbrick. Perhaps due to the king's short reign. The remains of statues representing Shepseskaf were found in the complex, confirming that the cult was indeed practiced. These statues are now in the Cairo Museum.