King Mentuhotep II | Last King of the 11th Dynasty

King Mentuhotep

In his domestic policy, Mentuhotep II tried to centralize the power of government in his capital, limit the powers of the provincial governors, and prevent the hereditary succession of provincial rule. Mentuhotep II succeeded in what he wanted, and the title “great provincial governor” and other huge titles that the provincial governors assumed for themselves in the first transition era disappeared, and the provincial governors no longer carved their tombs in their regions, but carved most of their tombs around the tombs of the kings in the west of the capital, Thebes.

Mentuhotep II weeded out disloyal elements and appointed his own Theban employees to important positions in the state. One of these employees served as governor of Lower Egypt, a new position necessitated by the fact that the capital was located in Thebes in the south.

Regarding the foreign policy of King Mentuhotep II, he sent an expedition to the Hammamet Valley that eliminated the sources of riots in this area, and he also reopened the road to the turquoise mines in Sinai, and regarding Egypt's western borders, he sent an expedition to the Libyan Tahnu tribes that managed to kill the leader of this tribe, and tried to restore the influence that Egypt had in Nubia at the end of the Sixth Dynasty.

Mentuhotep II ordered the construction of many temples, of which only a few have survived. Most of them were in Upper Egypt, specifically in Abydos, Aswan, Tod, Arment, Arment, Al-Jabalin, Kaab, Karnak, and Dendera. In accomplishing this, Mentuhotep followed a tradition started by his grandfather Intef II: Royal building activities in the regional temples of Upper Egypt began during the reign of Intef II and continued throughout the Middle Kingdom.

King Mentuhotep II was buried in the Theban necropolis at Deir el-Bahri. His funerary temple was one of the most ambitious architectural projects, incorporating many architectural and religious innovations. It contained covered terraces and corridors around the central building.

It was the first funerary temple in which the king was represented as Osir. His temple inspired the temples that came after him, such as the temple of Hatshepsut and the temple of Thutmose III of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The remains of his temple in Deir el-Bahri can still be found next to Hatshepsut's temple.

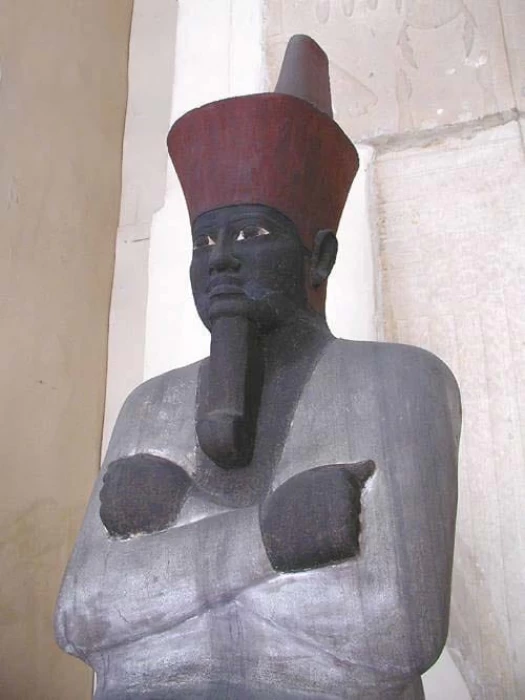

His most famous statue was found by Howard Carter - the discoverer of Tutankhamun's tomb - in 1900 by accident, when his horse stumbled into the outer courtyard of the king's funerary temple in Deir el-Bahri, west of Luxor. Carter found a well that led to a small chamber where he found this statue wrapped in linen.

In the statue, the king wears a red crown and a knitted robe for the Jubilee Year of Love Sid, which was celebrated after thirty years of the king's reign. The statue's body is colored black and its arms are crossed at the chest to associate it with Osiris, the god of death, fertility, and rebirth.