Costumes in Ancient Egypt

Clothing and Fashion in Ancient Egypt

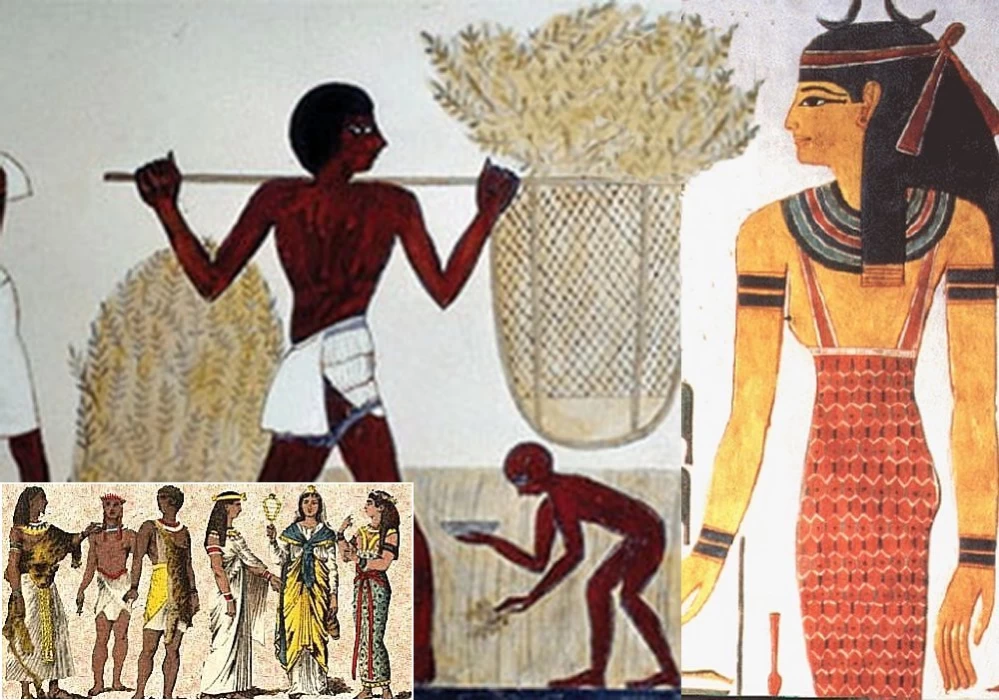

Fashion in Ancient Egypt refers to the clothing styles adopted by the Egyptians from the end of the Neolithic period, approximately 3100 B.C., until the fall of the Ptolemaic Kingdom with the death of Queen Cleopatra around 30 B.C. The garments of this period were notable for their vibrant colors and diverse fabrics, frequently adorned with precious stones and jewelry. Ancient Egyptian attire was designed not only for visual appeal but also for comfort, ensuring that wearers could remain cool in the harsh desert climate. Linen was the primary fabric used in Ancient Egyptian clothing, chosen for its capacity to alleviate the effects of the subtropical heat. This fabric is produced from the flax plant, with fibers extracted from its stem. The techniques of spinning, weaving, and sewing played a crucial role in Egyptian culture. While vegetable dyes were sometimes used on textiles, most clothing was generally left in its natural color. Although wool was acknowledged, it was considered impure, and only the wealthy could afford garments made from animal fibers, which were often subject to cultural restrictions. Wool was occasionally used for women's outer garments but was banned in temples and other sacred locations.

Individuals of lower social status, such as laborers and peasants, regularly wore Shinta, a linen garment that was widely used among the general population. Slaves often worked without any clothing. The most common headwear was referred to as khat or herbal, a striped fabric predominantly worn by men. During the period of the Pyramids, known as the Old Kingdom, which commenced around 2130 B.C., clothing was relatively simple. Men typically donned skirts called Shendyt, which were fastened at the waist and could be styled in various manners, including folding or gathering at the front. These skirts were relatively short during this time. In the following Middle Kingdom period, around 1600 B.C., the length of the skirts began to increase. By approximately 1420 B.C., garments such as lightweight jackets or long-sleeved blouses, along with longer dresses for women, became common. Throughout the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms, ancient Egyptian women primarily wore a straightforward garment known as Kalasiris. Women's clothing in ancient Egypt was generally more conservative than that of men, with dresses typically secured by one or two straps and extending to the ankle. The upper part of the dress could be adjusted to rest at the bust, and the length of the garment often indicated the wearer’s social standing. Women embellished their dresses with beads or feathers for decorative effect and frequently chose to wear shawls, capes, or robes. The shawl, crafted from fine linen, measured approximately 4 feet in width and 13 or 14 feet in length, and was typically styled in a pleated manner.

In ancient Egypt, it was customary for children to remain without clothing until they reached the age of six. Once they turned six, they were allowed to wear garments to protect themselves from the harsh climate. A common hairstyle for these children was the side-lock, which featured a section of uncut hair on the right side of the head. Although they were typically unclothed, children often adorned themselves with various forms of jewelry, such as anklets, bracelets, collars, and hair accessories. As they grew older, they began to emulate the fashion styles of their parents. In the context of ancient Egyptian attire, wigs were of considerable significance, especially among kings, rulers, and wealthy individuals of both sexes. These wigs were made using diverse techniques, sometimes incorporating human hair and at other times utilizing fibers from date palms. They were frequently styled in tight curls and narrow braids. Both men and women wore these wigs during special occasions, often embellished with cones of scented fat that melted to release delightful fragrances of perfumes and hair products.

Jewelry was highly esteemed in ancient Egypt, cutting across various social strata, from the wealthy elite to the less fortunate. These ornaments were generally large and somewhat heavy. The primary function of jewelry was to enhance aesthetic appeal, serving as a complement to the simple white linen attire preferred by the ancient Egyptians. They favored vibrant hues, shiny gemstones, and precious metals, as illustrated by the remarkable artifacts of King Tutankhamun housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. These exquisite pieces were made from materials sourced locally, including gold extracted from Egypt's eastern desert and Nubia, which remained an Egyptian territory for many centuries. In contrast, silver was a scarce resource, imported from Asia, and was often considered more precious than gold. The eastern desert also provided a crucial supply of colorful semi-precious stones such as carnelian, amethyst, and jasper. Turquoise was mined in the Sinai Peninsula, while the deep blue lapis lazuli was obtained from far-off Afghanistan. Furthermore, glass and faience—glazed materials derived from a base of stone or sand—were favored alternatives to natural stones due to their wide range of colors. The ancient Egyptians exhibited exceptional skill in crafting jewelry from turquoise and metals like gold and silver, as well as small beads. Both men and women adorned themselves with vividly colored earrings, necklaces, and other decorative items. Those who could not afford gold or precious stones often turned to creating jewelry from colored pottery beads, which were also artistically designed.

The practice of embalming significantly contributed to the development of cosmetics and perfumes. Ancient Egypt was famous for its luxurious and highly coveted perfumes, which ranked among the most expensive in the ancient world. Compared to other ancient cultures, the Egyptians were the most frequent users of makeup. They decorated their nails and hands with henna. A wealth of artifacts related to cosmetic preservation can be found in the Egyptian Museum, particularly in the esteemed collection of King Tutankhamun, which is accessible to visitors during regular museum tours. Black eyeliner, made from Galena, was used to enhance and define the eyes, while eye shadow was created from crushed malachite. The red pigment for lips, typically associated with women, was derived from ochre. These cosmetic formulations were often combined with animal fats to improve their texture and durability. Both genders applied Galena or powdered malachite not only for beauty but also due to the belief that it provided protection against dust and dirt. Research published by the American Chemical Society in the Journal of Analytical Chemistry indicated that the presence of lead in these cosmetics was intentional. The results imply that lead, when combined with naturally occurring body salts, generates nitric oxide, which is recognized for its immune-boosting properties. It is suggested that the ancient Egyptians intentionally designed these products to enhance immunity, potentially helping to prevent eye infections.

The footwear of that era was marked by a blend of practicality and sophistication, with distinct categories including civilian shoes, military boots, children's footwear—which were essentially scaled-down versions of adult designs—and the ornate shoes donned by nobility. Footwear was predominantly unisex, featuring leather sandals or, for the clergy, those crafted from papyrus. Since Egyptians often went barefoot, sandals were mainly utilized for special events or circumstances requiring foot protection.

A Brief Analysis of Policy, Cultural, and Historical MilieusThe costumes of ancient Egypt carry an immense weight in comprehending the social, cultural, and religious relations of one of the most complex civilizations in the world. Clothing played an essential role in the lives of the ancient Egyptians; it was not worn solely to cover the body. Rather, it signified social class, sex, occupation, and religion, all of which were in harmony with the surroundings and the sophisticated civilization that the people of the Nile River developed.

Linen is the Fabric of Choice in the ancient Egyptian clothes.

In ancient Egypt, one of the most popular and numerous textiles was the flax linen, which was predominantly cultivated along the banks of the Nile. The high temperatures in Egypt made it unavoidable to wear light and porous materials; hence, linen became the most appropriate material to use. All the same, the process of making linen from the flax plant was rather labor-intensive because it involved soaking the plant, pounding it down to retrieve fewer strands of it, and finally, yarn coming from those strands.

Zibellina esdromis fine-quality linen was especially popular with the nobles’ elite. The most advanced, termed "palace linen," was quite light but stable, glossy, and a bit transparent, indicating that it was designed for the affluent class. Nobility and priests, including the pharaohs, wore the most delicate and immaculate white linen attires, which were also for royalty due to their unblemished look and spiritual aspect, while the lower class dressed in the most tattered and coarse fabrics.

The clothing worn by the elite reflected their position, riches, and belief in their godliness. As earthly gods, the Queen and Pharaoh donned fashionable elements of clothing infused with various images. One of the most popular items of clothing worn by the pharaoh was the'shendyt’, a tailored pleated skirt that was extended with both gold and gem decorations. It was held in place by a decorative sash and, at times, was worn with a beautifully crafted robe or jacket for events.

Pharaohs also had a piece of headgear that was almost a statue of a king, called the ‘names’, which is a striped fabric wrapped around the head and tied at the back. All three, together with the false beard, the headdress of a king, and crowns with either the white or red crown of Egypt or the double crowns of Egypt—a sign of authority and power, only that it was royal power.

They wore clothes similar to those of the pharaoh but not as ostentatious. Richer men and women wore complex necklaces that included gold and colored stones. Their dresses were elaborately designed to exhibit their social class, with women frequently dressing in body-hugging sheaths made out of quality linen.

As the elites displayed their opulent clothing, the vast majority of the Egyptian population, consisting of farmers, laborers, artisans, and servants, put on simpler clothes. Working-class men were mostly found dressed in a simple loincloth or a knee-length coarser linen kilt. The tunic dresses worn by women were no exception and were specially designed to facilitate a woman's domestic and daily activities.

In spite of having simple clothing, it was clear that they took time and effort in the way they looked. The cleanliness and general appearance of the Egyptians of all social classes were important, and this can be attributed to the fact that they applied perfumes, oils, and cosmetics on a daily basis as part of their dressing code.

Religious and ceremonial costumes

Religious beliefs and practices permeated every aspect of daily life in ancient Egypt; hence, the costumes worn during religious and ceremonious activities depicted the outlook of the society. To express their sanctity and the god’s role they were playing, priests wore linen white robes. Most high priests were draped in leopard-skin cloaks, which were worn around the robe’s bust region during the ceremony to indicate closeness to the gods.

Dresses of deities were often characterized by very elaborate and expensive garments, with some, like goddess Hathor, even dressed in detailed sheath dresses. The meaning behind the use of practical animal skins and feathers, as well as ornamental pieces, was to call for the presence of divine beings and their goodwill.

Moreover, no attire in ancient Egypt would be complete without the inclusion of ornamental pieces. For the ancient Egyptians, jewelry had a purpose beyond mere decoration; it was considered to be a protective talisman worn against dark forces. Everyone, regardless of rank, embellished and decorated themselves with intricate pieces of jewelry, such as neckpieces, ear decorations, wrist and ankle covering ornaments, and even finger bands.

Rings, earrings, necklaces, and other kinds of jewelry were usually very expensive things because they were made from gold and other precious stones for the rich class, whereas the lower class spent less on ornamental copper, bronze, or colored glazed beads.

In the history of mankind, when different civilizations have flourished and left behind valuable artifacts, amulets have also been widely utilized among the ancient Egyptians. They were not merely decorative charms worn on a necklace or a bracelet, which was the fashion of the day; they also represented gods, animals, and other holy things believed to give protection in life and death.