Temple Of Hatshepsut

The Hatshepsut Mortuary Temple was built during the time of Pharaoh Hatshepsut of Egypt's Eighteenth Dynasty. It is regarded as an ancient architectural masterpiece, located directly across from Luxor. Its three huge terraces climb from the desert bottom to the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari. Hatshepsut's tomb, KV20, is located within the same massif capped by El Qurn, a pyramid for her funeral complex. The adjoining valley temple is located at the edge of the desert, 1 km (0.62 mi) east of the complex, and connected to it via a causeway. Across the River Nile

The entire edifice points to the enormous Eighth Pylon, Hatshepsut's most recognized addition to the Temple of Karnak and the departure point for the Beautiful Festival of the Valley procession. Its axes indicate the temple's twin functions: its central east-west axis received Amun-Reus bark during the festival's climax, and its north-south axis signified the pharaoh's life cycle from coronation to rebirth. The tiered temple was built during Hatshepsut's seventh and twenty regnal years, and the plans were continually changed. Its design was strongly influenced by the adjacent Eleventh Dynasty Temple of Mentuhotep II, which had been completed six centuries before

During the Amarna Period, Akhenaten ordered the temple's images of Egyptian gods, particularly those of Amun, to be removed. These damages were later rectified by Tutankhamun, Horemheb, and Ramesses II. An earthquake in the Third Intermediate Period inflicted additional damage. During the Ptolemaic dynasty, the Amun sanctuary was restructured, and a new portico was constructed at its entrance.

The temple resurfaces in modern records in 1737, when Richard Pococke, a British explorer, visited the site. Several visits followed, but significant excavation did not begin until the 1850s and 1960s, under Auguste Mariette. The temple was entirely excavated between 1893 and 1906 as part of an Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF) mission led by Édouard Naville. Herbert E. Winlock and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) made additional attempts from 1911 to 1936, as did Émile Baraize and the Egyptian Antiquities Service (now the Supreme Council of Antiquities) from 1925 to 1952. Since 1961, the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology (PCMA) has completed substantial consolidation and restoration operations throughout the temple, which was inaugurated.

The opening feature of the temple is the three terraces fronted by a portico leading up to the temple proper and arrived at by a 1 km (0.62 mi) long causeway that led from the valley temple. Each elevated terrace was accessed via a ramp that separated the porticoes The lower terrace is 120 m (390 ft) deep and 75 m (246 ft) broad, surrounded by a wall with a single 2 m (6.6 ft) wide access gate in the center of its east side. This terrace included two Persea (Mimusops schimperi) trees, two T-shaped basins for papyri and flowers, and two reclining lion statues on the ramp balustrade. The lower terrace's 25 m (82 ft) broad porticoes each have 22 columns placed in two rows, with relief scenes on their walls. The reliefs on the south portico portray the transfer of two obelisks from Elephantine to Thebes' Temple of Karnak, where Hatshepsut presents the obelisks and temple to Amun-Re. They also show Dedwen. Lord of Nubia and the 'Foundation Ritual': The north portico's reliefs depict Hatshepsut as a sphinx crushing her enemies, along with images of fishing and hunting, and offerings to the gods.

The middle terrace is 75 meters (246 feet) deep and 90 meters (300 feet) broad, with porticoes on the west and partially on the north sides. The west porticoes have 22 columns organized in two rows, while the north portico has 15 columns in a single row. The reliefs on the west porticoes of this terrace are the most outstanding from the funerary temple. The southwest portico shows the trip to the Land of Punt, as well as the transfer of exotic commodities to Thebes.

Hathor is significant at Thebes because she represents the hills of Deir el-Bahari, as well as Hatshepsut, who claimed to be a reincarnation of the goddess. Hathor is also associated with Punt, which is the subject of reliefs in the nearby portico. At the north end of the middle terrace is a shrine dedicated to the god Anubis

The second chamber had an Amun cult picture and was flanked on either side by a chapel. The reliefs in the north chapel portray the gods of the Heliopolitan Ennead, while those in the south chapel depict the gods of the Theban Ennead. Each of the enthroned gods carried a scepter and an ankh. Atum and Montu occupied the end walls while presiding over the delegations The third chamber included a statue around which the 'Daily Ritual' was done. It was said to have been built a millennium after the initial temple, dubbed 'the Ptolemaic Sanctuary' by Ptolemy VIII Euergetes. The finding of reliefs representing Hatshepsut, on the other hand, confirms that the structure was built during her reign. Egyptologist Dieter Arnold speculates that it may have housed a stone fake door.

The entrance leads to the main court, which features a large altar open to the sky and accessible via a staircase to the court's west The court has two niches on the south and west walls. The former depicts Ra-Horakhty offering an ankh to Hatshepsut, while the latter has a relief of Hatshepsut as a priest of her religion. A chapel[e] was attached to the court and featured representations of Hatshepsut's family. In these, Thutmose I and his mother, Seniseneb, are depicted giving offerings to Anubis, while Hatshepsut and Ahmose are depicted giving offerings to Amun-Re Situated in the south of the courtyard was the mortuary cult complex. Accessed through a vestibule adorned with three columns are two offering halls oriented on an east-west axis. The northern hall is dedicated to Thutmose I; the southern hall is dedicated to Hatshepsut. Hatshepsut's offering hall emulated those found in the mortuary temples of the Old and Middle Kingdom pyramid complexes

The Beautiful Festival of the Valley, which began in the Temple of Karnak and ended at Amun's sanctuary, was held annually. This event originated in the Middle Kingdom and culminated at Mentuhotep II's temple. The procession began at Karnak's Eighth Pylon, headed by Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, and was followed by noblemen and priests carrying Amun's bark, accompanied by musicians, dancers, courtiers, and additional priests, and guarded by troops. A fleet of small boats and the large ship Userhat, which carried the barque, were towed In Hatshepsut's time, the Amun bark was a miniature version of a transport barge, with three long carrying poles each handled by six priests.

Thutmose III proscribes Hatshepsut. Two decades after her death, in Thutmose III's forty-second regnal year, he resolved to remove any evidence of her rule as Egypt's pharaoh. His reasons for ending her reign are unclear. This challenge to her power, however, was short-lived. The proscription was abandoned two years later, when Amenhotep II ascended to the throne, leaving much of the erasure unfinished.

The third instance considers the likelihood of a dynastic dispute between the Ahmosid and Thutmosid dynasties. Thutmose III may have ensured that his son, Amenhotep II, would succeed to the throne by expunging her reign from history. There is, however, no known Ahmosid pretender Thutmose III used a variety of erasing procedures at her temple during his campaign. The scratching out of feminine pronouns and prefixes was the least destructive, as the text remained intact.

After Thutmose III died, the temple continued to be used for worship. During the Amarna Period, Akhenaten ordered the further erasing of the reliefs, with depictions of the gods, particularly Amun, being the object of this persecution. Early in his reign, Aten, a sun deity, was raised to the position of supreme god. The persecution of other gods did not begin immediately; instead, reform was implemented gradually over several years, culminating in prohibition around his ninth regnal year. The proscription correlates with Horus' ostracization.

Latest Articles

Admin

Regin of Abbas I of Egypt | Abbas Pasha I

Abbas has been often described as a mere voluptuary, but Nubar Pasha spoke of him as a true gentleman of the "old school". He was seen as reactionary, morose and taciturn, and spent nearly all his time in his palace. He undid, as far as lay in his power, the works of his grandfather, both good and bad.

Admin

Story of Gabal Shayeb Al Banat - Red Sea Mountain

Jabal shayb al-banat is one of the Red Sea Mountains in the eastern desert in Egypt, located to the west of the city of Hurghada at a latitude of 27 degrees north and a longitude of 33.5 degrees east of the Greenwich line approximately, this mountain is the highest mountain peak in the eastern desert with a height of up to 2185 meters, it is a prominent mass of igneous rocks

Admin

Neper God Of Grain

Neper was the deity of grains, particularly cereals that were important in Ancient Egypt, such as wheat and barley. It was stated that he foretold when the crops would grow, be harvested, and disappear.

Admin

Badr Museum in Farafra

The Badr Museum is located in a mud building, which is the common home found in this medieval part of Egypt. All of the artwork that was created by the artist is quite unique. His work almost always depicts life in the Farafra Oasis and he provides the work through both painting and sculpting.

Admin

The Black Head Temple

The Black Head Temple is a small temple dedicated to the worship of the goddess Isis and was discovered in 1936, by chance, in the Black Head area, which is now located within the Mandara area of the Montazah district in Alexandria. This temple was moved from its original place to the Latin Necropolis in 1994.

Admin

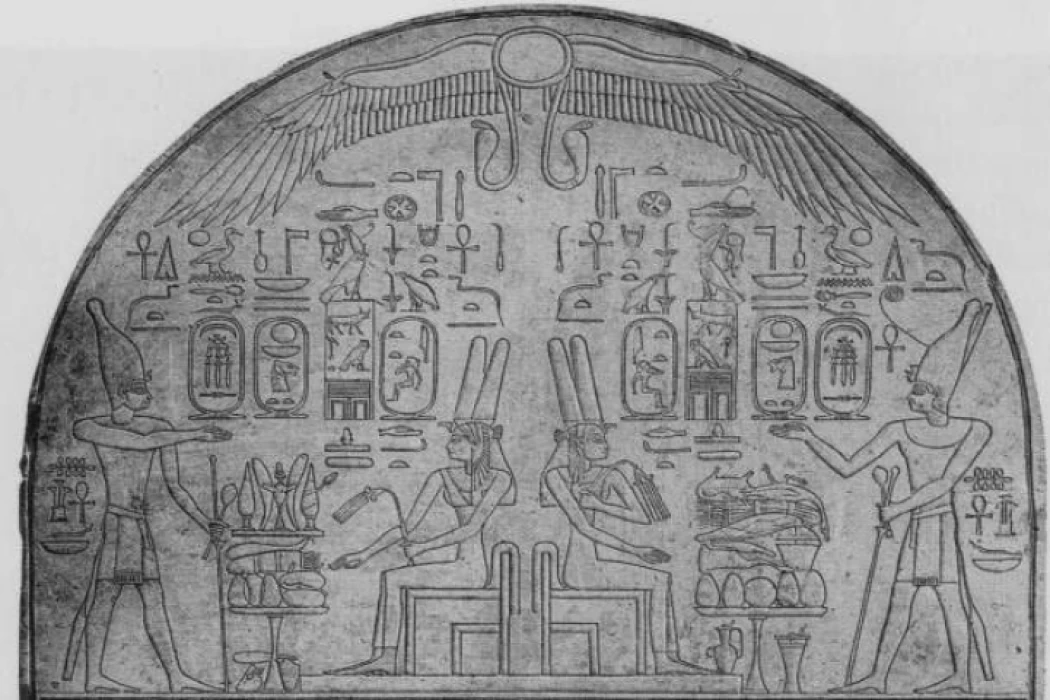

The Queen Tetisheri

Tetisheri was the mother of Seqenenre Tao, Queen Ahhotep I, and possibly Kamose. For sure, she was the mother of Satdjehuty/Satibu, as attested on the rishi coffin of the latter. At Abydos, her grandson King Ahmose I erected a Stela of Queen Tetisheri to announce the construction of a pyramid and a "house" for Tetisheri.