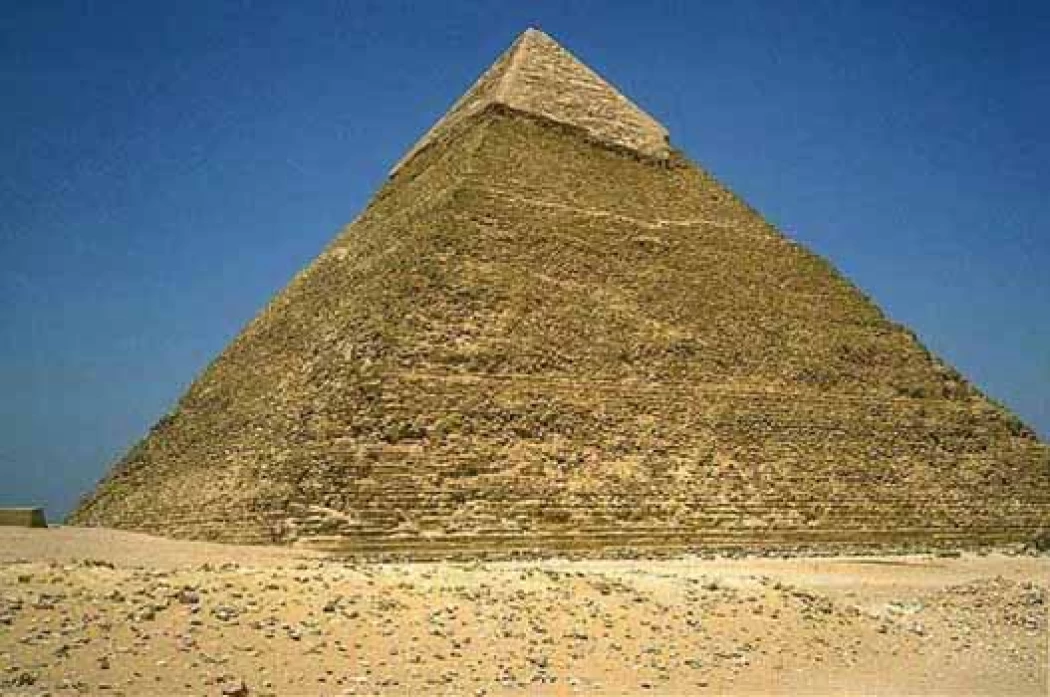

King Cheops owner of the Great pyramid

Khufu, also known as Cheops, was the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty during the first half of the Old Kingdom period (26th century BC). He died around 2566 BC. Khufu succeeded his father, Sneferu, as king. He is widely acknowledged to have commissioned the Great Pyramid of Giza, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, although many other features of his reign are inadequately documented.

The only totally preserved portrait of the king is a tiny ivory figurine discovered in a later-period temple ruin at Abydos in 1903. All other reliefs and statues were unearthed in fragments, and many Khufu buildings have been gone. Everything we know about Khufu comes from inscriptions in his necropolis at Giza and later writings.[citation needed] For example, Khufu is the prominent character mentioned in the Westcar Papyrus from the 13th dynasty.

The majority of writings on King Khufu were recorded by ancient Egyptian and Greek historians around 300 BC.[citation needed]. Khufu's obituary is portrayed in a contradictory manner: while the monarch enjoyed long-term cultural heritage preservation over the Old and New Kingdom periods, the ancient historians Manetho, Diodorus, and Herodotus paint a very bad picture of Khufu's character. As a result, an uncertain and critical portrayal of Khufu's personality persists.

Khufu's name was given to the god Khnum, which may indicate a rise in Khnum's popularity and religious significance. Various royal and religious titles adopted around this time may indicate that Egyptian pharaohs attempted to emphasize their divine origin and status by dedicating their cartouche names (official royal names) to certain deities. Khufu may have seen himself as a heavenly creator, a role already assigned to Khnum, the god of creation and expansion. As a result, the monarch united Khnum's name to his own. Khufu's full name (Khnum-Khufu) translates as "Khnum protect me While contemporary Egyptological pronunciation gives his name as Khufu,

The pharaoh officially used two versions of his birth name: Khnum-Khufu and Khufu. The first (complete) version exhibits Khufu's religious loyalty to Khnum, but the second (shorter) version does not. It is unknown as to why the king would use a shortened name version since it hides the name of Khnum and the king's name connection to this god. It might be possible though, that the short name was not meant to be connected to any god at all

Khufu is also known as Χέoψ, Khéops, or Cheops by Diodorus and Herodotus) and Σοῦφις Josephus used the unusual variant of Khufu's name, Σόφε, (The pronunciations listed here are for English; the pronunciations in Ancient Greek were different.) Arab historians wrote mystic myths about Khufu and the Giza pyramids.

The royal family of Khufu was fairly extensive. It is uncertain whether Khufu was Sneferu's biological son. Egyptologists believe Sneferu was Khufu's father, but only because later historians established that the eldest son or a chosen descendant would inherit the throne.[9] In 1925, the tomb of Queen Hetepheres I, G 7000x, was discovered east of Khufu's pyramid.

It included several valuable grave goods, and several inscriptions gave her the title Mut-nest (meaning "mother of a king"), as well as the name of King Sneferu. Initially, it appeared that Hetepheres was Sneferu's wife and that they were Khufu's parents. More recently, however, some have questioned this theory because Hetepheres is not known to have had the title Hemet-nest (meaning "king's wife"), which is required to authenticate a queen's royal rank.

Instead of the spouse's title, Hetepheres was given the title Sat- netjer- khetef (verbatim: "daughter of his divine body"; symbolically: "king's bodily daughter"), which was used for the first time. As a result, researchers believe Khufu was not Sneferu's biological son, but rather that Sneferu legitimized Khufu's rank and familial standing through marriage. Khufu established his new title by apotheosizing his mother as the daughter of a living deity. This notion may be reinforced by the fact that Khufu's mother was buried next to her son rather than in her husband's necropolis, as was expected.

Latest Articles

Admin

Neper God Of Grain

Neper was the deity of grains, particularly cereals that were important in Ancient Egypt, such as wheat and barley. It was stated that he foretold when the crops would grow, be harvested, and disappear.

Admin

Djoser

Djoser was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom and was the founder of that epoch. He is also known by his Hellenized names Tosorthros (from Manetho) and Sesorthos (from Eusebius). He was the son of King Khasekhemwy and Queen Nimaathap, but whether he was also the direct successor to their throne is unclear. Most Ramesside king lists identify a king named Nebka as preceding him, but there are difficulties in connecting that name with contemporary Horus names, so some Egyptologists question the received throne sequence. Djoser is known for his step pyramid, which is the earliest colossal stone building in ancient Egypt

Admin

Kom Al Dikka Alexandria

Kom El Deka, also known as Kom el-Dikka, is a neighborhood and archaeological site in Alexandria, Egypt. Early Kom El-Dikka was a well-off residential area, and later it was a major civic center in Alexandria, with a bath complex (thermae), auditoria (lecture halls), and a theatre.

Admin

The God Anuket

Anuket, in Egyptian religion, the patron deity of the Nile River. Anuket is normally depicted as a beautiful woman wearing a crown of reeds and ostrich feathers and accompanied by a gazelle.

Admin

The Red Chapel of Hatshepsut

The Red Chapel of Hatshepsut or the Chapelle rouge was a religious shrine in Ancient Egypt. The chapel was originally constructed as a barque shrine during the reign of Hatshepsut. She was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty from approximately 1479 to 1458 BC.

Admin

The Serapeum of Alexandria

The Serapeum of Alexandria in the Ptolemaic Kingdom was an ancient Greek temple built by Ptolemy III Euergetes (reigned 246–222 BC) and dedicated to Serapis, who was made the protector of Alexandria, Egypt. There are also signs of Harpocrates. It has been referred to as the daughter of the Library of Alexandria.