Historical Cairo

Islamic Cairo, romanized: Qāhira al-Muʿizz, lit. 'Al-Mu'izz's Cairo'), or Medieval Cairo, officially Historic Cairo ( al-Qāhira tārīkhiyya), refers to the areas of Cairo, Egypt, that were built from the Muslim conquest in 641 CE until the term "Islamic" Cairo refers not to a greater presence of Muslims in the area, but to the city's rich history and heritage from its founding in the early period of Islam, distinguishing it from the nearby Ancient Egyptian sites of Giza and Memphis. This area has one of the most extensive and dense concentrations of historic buildings in the Islamic world. It is distinguished by hundreds of mosques, tombs, madrasas, villas, caravanserais, and fortifications built during Egypt's Islamic era.

In 1979, UNESCO designated Historic Cairo as a World Cultural Heritage site, describing it as "one of the world's oldest Islamic cities, with its famous mosques, madrasas, hammams, and fountains" and "the new center of the Islamic world, reaching its golden age in the 14th century."Cairo's history begins with Muslim Arabs conquering Egypt in 640, led by General 'Amr ibn al-'As. Although Alexandria was Egypt's capital at the time (and had been throughout the Ptolemaic, Roman, and Byzantine periods), the Arab invaders chose to create a new city called Fustat as Egypt's administrative capital and military garrison hub. The new city was constructed near a Roman-Byzantine castle known as Babylon on the banks of the Nile (today located in Old Cairo) Southwest of the later Cairo proper (see below).

This location may have been chosen for various reasons, including its slightly closer proximity to Arabia and Mecca, fear of strong remaining Christian and Hellenistic influence in Alexandria, and Alexandria's vulnerability to Byzantine counteroffensives arriving by sea (which did occur). Perhaps more importantly, Fustat's location at the intersection of Lower Egypt (the Nile Delta) and Upper Egypt (the Nile Valley further south) made it a strategic point from which to control a country centered on the Nile, much like the Ancient Egyptian city of Memphis (located just south of Cairo today).southwest of what would become Cairo proper. This location could have been chosen for various reasons, including its slightly greater proximity to Arabia and Mecca, fears about substantial lingering Christian and Hellenistic influence in Alexandria, and Alexandria's vulnerability to Byzantine counteroffensives arriving by sea. Perhaps more importantly, Fustat's location at the intersection of Lower Egypt (the Nile Delta) and Upper Egypt (the Nile Valley further south) made it a strategic point from which to control a Nile-centered country, similar to the Ancient Egyptian city of Memphis (located just south of Cairo today). Fustat soon grew to become Egypt's primary metropolis, port, and economic center, while Alexandria became more of a regional town. The Umayyads took control of the Islamic world in 661, with their capital in Damascus, until they were overthrown by the Abbasids in 750. Marwan II, the last Umayyad caliph, made his final stand in Egypt before being assassinated on August 1, 750. Egypt and Fustat were thereafter taken over by the Abbasids.

Ahmad Ibn Tulun was a Turkish military commander who served the Abbasid caliphs in Samarra during a prolonged crisis of Abbasid power. He became Egypt's governor in 868, but swiftly became its de facto ruler, recognizing the Abbasid caliph's symbolic power. He became so powerful that the caliph eventually enabled him to assume control of Syria in 878. During this period of Tulunid power (under Ibn Tulun and his sons), Egypt gained independence for the first time since Roman control in 30 BC. In 870, Ibn Tulun established his administrative center, al-Qata'i, located immediately northwest of al-Askar.Ibn Tulun died in 884, and his sons governed for a few more decades until 905, when the Abbasids sent an army to reestablish direct control and destroyed down al-Qata'i, leaving only the mosque standing. Following this, Egypt was dominated by another dynasty, the Ikhshidids, who served as Abbasid governors from 935 to 969.

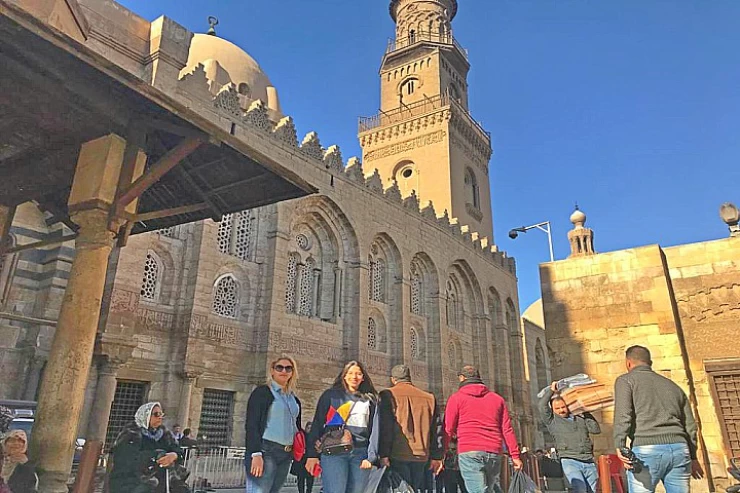

The city was termed al-Mu'izziyya al-Qaahirah, the "Victorious City of al-Mu'izz", then simply called "al-Qahira", which gave us the contemporary name of Cairo. The city was located northeast of Fustat and the previous administrative capitals established by Ibn Tulun and the Abbasids. Jawhar planned the new city around the Great Palaces, which housed the caliphs, their households, and the state's institutions. Two principal palaces were completed: an eastern (the larger of the two) and a western one, separated by an important plaza known as Bayn al-Qasrayn ("Between the Two Palaces"). The Mosque of al-Azhar, the city's major mosque, was established in 972 as both a Friday mosque and a center of scholarship and instruction and is now regarded as one of the world's oldest colleges. The city's main roadway, known today as Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah roadway (or al-Mu'zz Street), but traditionally known as the Qasabah or Qasaba, extended from one of the northern city gates (Bab al-Futuh) to the southern gate (Bab Zuweila) and connected the palaces via Bayn al-Qasrayn. Under the Fatimids, however, Cairo was a royal metropolis that was restricted to the general public and inhabited solely by the Caliph's family, state officials, army regiments, and other personnel required to run the system and its city. For a while, Fustat was Egypt's primary economic and urban center. Only later did Cairo expand to include other neighboring cities, notably Fustat, yet the year 969 is frequently regarded the "founding year" of the current city.

Al-Mu'izz and the Fatimid Caliphate's administrative apparatus left their former capital, Mahdia, Tunisia, in 972 and landed in Cairo in June 973.[9][6] The Fatimid Empire swiftly became powerful enough to pose a threat to the competing Sunni Abbasid Caliphate. During the longest tenure of any Muslim ruler, Caliph al-Mustansir (1036-1094), the Fatimid Empire reached its apex but also began to fall. A few powerful viziers acting on behalf of the caliphs were able to restore the empire's power on occasion. The Armenian vizier Badr al-Jamali (in office from 1073-1094) is notable for rebuilding Cairo's walls in stone, with huge gates that still stand today and were expanded under later Ayyubid authority. The late eleventh century was also a period of significant events and changes in the region. At this time, the Great Seljuk (Turkish) Empire seized control of much of the eastern Islamic world. The entrance of the Turks, who were primarily Sunni Muslims, played a long-term role in the so-called "Sunni Revival," which halted the Fatimids' and Shi'a factions' advances in the Middle East. In 1099, the First Crusade seized Jerusalem, and the new Crusader powers posed an unexpected and significant danger to Egypt. New Muslim rulers, such as Nur al-Din of the Turkish Zengid dynasty, led the overall onslaught against the Crusaders.

The Fatimids' weakness became so severe in the 12th century that the last Fatmid Caliph, al-'Adid, asked the Zengids for assistance in protecting themselves from the King of Jerusalem, Amalric, while also attempting to collude with the latter to keep the Zengids in check. In 1168, as the Crusaders marched on Cairo, the Fatimid vizier Shawar, concerned that the unfortified city of Fustat would be used as a base for besieging Cairo, ordered its evacuation and then set it on fire.

Salah ad-Din's reign saw the rise of the Ayyubid dynasty, which dominated Egypt and Syria while continuing the fight against the Crusaders. He also began construction of an ambitious new fortified Citadel (the modern Citadel of Cairo) further south, beyond the walled city, which would house Egypt's monarchs and state government for generations to come. This ended Cairo's status as an elite palace city and began a process by which the city became an economic center inhabited by ordinary Egyptians and available to international visitors. Cairo grew into a major urban hub over the centuries. Fustat's decline throughout the same period opened the stage for its ascent. The Ayyubid sultans and their Mamluk successors, Sunni Muslims seeking to eliminate the Shi'a Fatimids' power, gradually dismantled and rebuilt the vast Fatimid palaces with their structures. The Al-Azhar Mosque was turned into a Sunni institution, and it is now the leading center for studying the Qur'an and Islamic law in the Sunni Muslim world.

In 1250, the Ayyubid monarchy fell apart, and sovereignty passed to the Mamluks. The mamluks were soldiers who were bought as young slaves (typically from diverse regions of Central Eurasia) and trained to serve in the sultan's army. They formed a cornerstone of the Ayyubid military under Sultan al-Salih, eventually gaining enough force to seize control of the realm during the Seventh Crusade. Between 1250 and 1517, the throne was passed down from one mamluk to the next under a system of succession that was primarily non-hereditary but frequently violent and chaotic. Nonetheless, the Mamluk Empire carried on many of the traditions of the Ayyubid Empire before it, and it was responsible for halting the Mongol invasion in 1260 (most famously at the Battle of Ain Jalut) and putting an end to the Crusader nations in the Levant.

Cairo achieved its demographic and income pinnacle during the reign of Mamluk sultan al-Nasir Muhammad (1293–1341, including interregnums). Although difficult to quantify, a widely acknowledged estimate of Cairo's population around the conclusion of his reign puts it at around 500,000, making it the world's largest city outside of China at the time. Despite being primarily a military caste, the Mamluks were active builders and patrons of religious and municipal structures. Many of Cairo's most impressive historical monuments were built during their time.The city also benefited from its control of commercial routes connecting the Indian Ocean with the Mediterranean.[6] Following al-Nasir's reign, Egypt and Cairo had recurrent plague epidemics, beginning with the Black Death in the mid-14th century. Cairo's population fell and took decades to recover, yet it remained the Middle East's largest metropolis.

Under the Ayyubids and later the Mamluks, Qasaba Avenue became a preferred location for the construction of religious complexes, royal mausoleums, and commercial businesses, which were typically sponsored by the sultan or members of the ruling elite. This is also where Cairo's big souqs emerged, becoming the city's primary economic zone for international trade and commerce. As the main street became saturated with shops and space for further development there ran out, new commercial structures were built further east, close to al-Azhar Mosque and to the shrine of al-Hussein, where the souq area of Khan al-Khalili, still present today, progressively developed The increasing number of waqf establishments, particularly during the Mamluk period, contributed significantly to the development of Cairo's urban character. Waqfs were charitable trusts established under Islamic law to govern the function, operations, and financing sources of the ruling elite's numerous religious and civic institutions. They were often used to identify elaborate religious or civic structures that served several functions (e.g., mosque, madrasa, tomb, Erbil) and were frequently sponsored by profits from urban commercial buildings or rural agricultural estates.By the late 15th century, Cairo featured high-rise mixed-use buildings (known as a rab', a khan, or a wikala, depending on their specific use), with the two lower floors commonly used for commerce and storage purposes and the numerous levels above them rented out to tenants.

The Ottoman Empire conquered Egypt in 1517 under Selim I, and it remained under Ottoman administration for centuries. During this time, local elites fought tooth and nail for political power and influence; some were of Ottoman ancestry, while others belonged to the Mamluk caste, which persisted as part of the country's elites despite the demise of the Mamluk sultanate.

Cairo remained a prominent economic hub and one of the empire's most significant cities. It remains the primary staging site for the pilgrimage route to Mecca.[6] While the Ottoman governors were not major patrons of architecture like the Mamluks, Cairo nonetheless continued to develop and new neighborhoods did grow outside the old city walls.Ottoman architecture in Cairo remained significantly influenced and derived from local Mamluk-era traditions, rather than representing a decisive rupture with the past.[3] Some people, such as Abd ar-Rahman Katkhuda al-Qazdaghli, a mamluk official among the Janissaries in the 18th century, were avid architectural supporters.[6][3] Many of Cairo's historic bourgeois or aristocratic residences, as well as a handful of sabil-kuttabs, date back to the Ottoman Empire.

Napoleon's French forces briefly controlled Egypt from 1798 to 1801, following which an Albanian soldier in the Ottoman army named Muhammad Ali Pasha established Cairo as the capital of an autonomous kingdom that lasted from 1805 to 1882. The city then came under British rule until Egypt gained independence in 1922. Napoleon's French armies briefly ruled Egypt from 1798 to 1801, at which point an Albanian officer in the Ottoman army named Muhammad Ali Pasha created Cairo as the capital of an autonomous kingdom that lasted from 1805 until 1882. The city then fell under British authority until Egypt attained independence in 1922.

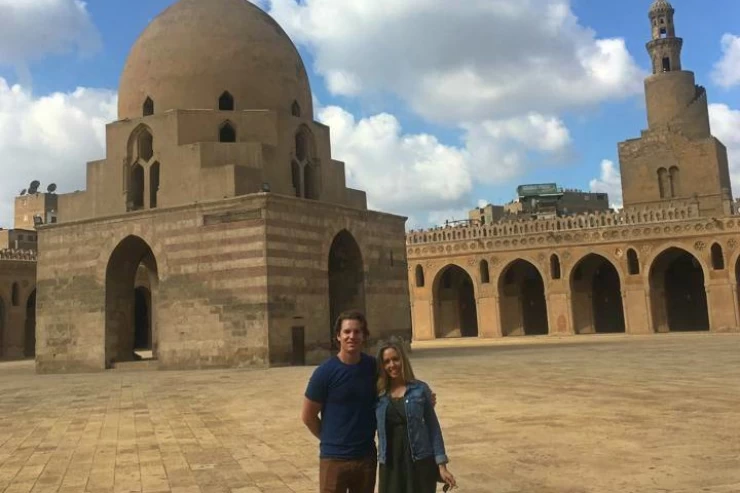

While the first mosque in Egypt was the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Fustat, the Mosque of Ibn Tulun is the oldest mosque to have retained its original shape and is a remarkable example of Abbasid architecture from the classical age of Islamic civilization. It was constructed between 876 and 879 AD in an architectural style inspired by the Abbasid capital of Samarra in Iraq. It is one of Cairo's largest mosques and is frequently recognized as one of the most beautiful.

The Mosque of al-Azhar, built in 970 AD, is one of the most important and long-lasting institutions of the Fatimid period, competing with Fes' Qarawiyyin for the title of the world's oldest university. Today, al-Azhar University is the world's leading center of Islamic learning and one of Egypt's largest universities, with campuses around the country. The mosque preserves many Fatimid components, but it has been added to and expanded over the years, most notably by the Mamluk sultans Qaitbay and al-Ghuri, and by Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda in the 18th century. The enormous Mosque of al-Hakim, the al-Aqmar Mosque, the Juyushi Mosque, the Lulua Mosque, and the Salih Tala'i Mosque are among the other Fatimid monuments that have survived.

When the Fatimid Caliphate established Cairo as a palace city in 969, a Fatimid general named Gawhar al-Siqilli oversaw the construction of the city's original mudbrick walls Later, in the late 11th century, the Fatimid vizier Badr al-Gamali ordered a restoration of the walls made mostly of stone and extended further outward than before to increase the space within Cairo's walls. There were many gates around the walls of Fatimid Cairo, but only three survive today: Bab al-Nasr, Bab al-Futuh, and Bab Zuwayla (where "Bab" means "gate". From 2001 to 2003, a restoration project successfully repaired the three gates and sections of the northern wall between Bab al-Nasr and Bab al-Futuh. Bab al-Nasr and Bab al-Futuh are both located on the northern segment of the wall, approximately two hundred yards apart.[24] The third surviving gate, Bab Zuwayla, is located in the southern section of the wall and is crowned by two minarets built in the 15th century.

Salah ad-Din (Saladin), the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, renovated and/or rebuilt the Fatimid walls and gates about 1170[25] or 1171. In 1176, he began working on a proposal to significantly increase the city's walls. This project comprised the construction of the Cairo Citadel as well as a 20-kilometer-long wall to connect and protect Cairo (the previous royal city of the Fatimid caliphs) and Fustat (Egypt's principal metropolis and former capital, located to the southwest). The full planned course of the wall was never completed, although extensive parts of the wall were built, including the section to the north of the Citadel and a section near Fustat in the south.

One of the city's eastern gates, which was part of the Ayyubid wall restoration, was also discovered in 1998 and has since been examined and rebuilt. It boasts a complicated defensive layout, which includes a bent entrance and a bridge over a moat or ditch. Initially designated as Bab al-Barqiyya, it is believed that it was once known as Bab al-Jadid ("New Gate"), one of the three eastern gateways recorded by al-Maqrizi In 1176, Salah ad-Din began building on a large Citadel to serve as Egypt's seat of authority, which was completed by his successors. It is situated on a peninsula in the adjacent Muqattam Hills that overlooks the city. The Citadel was the residence of Egypt's monarchs until the late nineteenth century, and it was constantly altered by successive rulers. Notably, Muhammad Ali Pasha constructed the 19th-century Mosque of Muhammad Ali, which still dominates the city skyline from its hilltop position.

Because trade and business played such an essential role in Cairo's economy, the Mamluks and later Ottomans constructed wikalas (caravanserais; also known as khans) to shelter merchants and products. The most notable and well-preserved example is the Wikala al-Ghuri, which today holds regular performances by the Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe. Another example of medieval commercial architecture is Radwan Bay's 17th-century Qasaba, which is now part of the al-Khayamiyya neighborhood, named for the decorative textiles (khayamiyya) that are being sold there.

Much of this ancient district is neglected and decaying, and it is one of Cairo's poorest and most populated neighborhoods. Furthermore, thefts of Islamic monuments and antiques in the Al-Darb al-Ahmar region jeopardize their long-term preservation. Various efforts to restore historic Cairo have been underway in recent decades, involving both Egyptian government officials and non-governmental groups such as the Aga Khan Trust for Culture In 1998, the government established the Historic Cairo Restoration Project (HCRP), which sought to rehabilitate 149 historical landmarks. In the years that followed, the HCRP oversaw various repairs in the area between Bab Zuweila and Bab Futuh, particularly around al-Mu'izz Street. Independent Egyptian conservators finished the repair of Bay al-Suhaymi and the Darb al-Asfar street in front of it in 1999, with financing from Kuwait's Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development. 237 In 2010, around 100 of the 149 monuments

The HCRP has also been chastised for establishing an open-air museum aimed at tourists while providing minimal benefits to the neighboring community. Around the same time, the AKTC began another effort aimed at revitalizing the Al-Darb al-Ahmar neighborhood with the completion of the adjoining Al-Azhar Park. This project intended for a more bottom-up approach to improving the community's urban fabric and residents' socioeconomic status, as well as more public and private participation.

More recent restoration efforts include the repair of the 14th-century Mosque of Amir al-Maridani in Al-Darb al-Ahmar, which began in 2018 and was completed in 2021, with the AKTC leading the project and the European Union providing extra funds. Between 2009 and 2015, the World Monuments Fund and the AKTC restored the 14th-century Amir Aqsunqur Mosque (also known as the Blue Mosque). Another project, finished in 2021, rebuilt Ruqayya Dudu's 18th-century Sabil-kuttab in the Suq al-Silah region. In 2021, the Egyptian government launched a new initiative to rehabilitate the old city, particularly the districts surrounding the historic city gates, to increase tourism. The effort would also involve restoring buildings that are not officially listed as monuments and pedestrianizing some zones. In some cases, the owners or tenants of certain buildings have been relocated elsewhere while restoration is ongoing.

Latest Articles

Admin

Neper God Of Grain

Neper was the deity of grains, particularly cereals that were important in Ancient Egypt, such as wheat and barley. It was stated that he foretold when the crops would grow, be harvested, and disappear.

Admin

Djoser

Djoser was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom and was the founder of that epoch. He is also known by his Hellenized names Tosorthros (from Manetho) and Sesorthos (from Eusebius). He was the son of King Khasekhemwy and Queen Nimaathap, but whether he was also the direct successor to their throne is unclear. Most Ramesside king lists identify a king named Nebka as preceding him, but there are difficulties in connecting that name with contemporary Horus names, so some Egyptologists question the received throne sequence. Djoser is known for his step pyramid, which is the earliest colossal stone building in ancient Egypt

Admin

Kom Al Dikka Alexandria

Kom El Deka, also known as Kom el-Dikka, is a neighborhood and archaeological site in Alexandria, Egypt. Early Kom El-Dikka was a well-off residential area, and later it was a major civic center in Alexandria, with a bath complex (thermae), auditoria (lecture halls), and a theatre.

Admin

The God Anuket

Anuket, in Egyptian religion, the patron deity of the Nile River. Anuket is normally depicted as a beautiful woman wearing a crown of reeds and ostrich feathers and accompanied by a gazelle.

Admin

The Red Chapel of Hatshepsut

The Red Chapel of Hatshepsut or the Chapelle rouge was a religious shrine in Ancient Egypt. The chapel was originally constructed as a barque shrine during the reign of Hatshepsut. She was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty from approximately 1479 to 1458 BC.

Admin

The Serapeum of Alexandria

The Serapeum of Alexandria in the Ptolemaic Kingdom was an ancient Greek temple built by Ptolemy III Euergetes (reigned 246–222 BC) and dedicated to Serapis, who was made the protector of Alexandria, Egypt. There are also signs of Harpocrates. It has been referred to as the daughter of the Library of Alexandria.