The Rosetta Stone | Discovery of Ancient Egypt Language

The Rosetta Stone

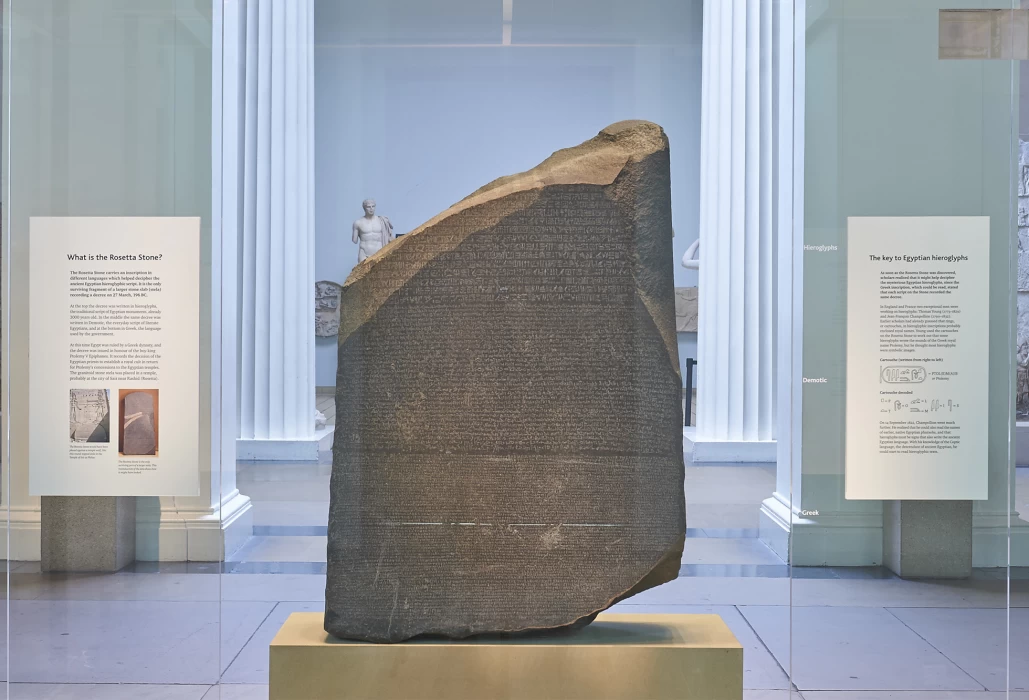

Following the emperor traveled scientists with the task of discovering and studying the remains of ancient Egyptian civilizations. Among the objects collected during the Napoleonic expedition was this block of granite on which a dedication to the pharaoh Ptolemy V Epiphore was engraved in three different characters:

hieroglyphic, the first writing used in Egypt, demotic and in Greek, spoken by the ruling dynasty, and which was of great importance in interpreting Egyptian writing.

Since the stone was found near the city of Rosetta, on the Nile, it was called the Rosetta Stone.

Discovery of Ancient Egypt Language

The two great personalities who engaged in the work of deciphering the stela were the English physicist Thomas Young and the French linguist Jean-Francois Champollion.

By 1819 Young was ahead of his French rival, having already deciphered the Demolithic text, identifying the symbols for Cleopatra and Ptolemy.

A few years later, in 1822, through careful comparisons with other texts, Champollion (a true linguistic genius who began the study of oriental languages at the age of eleven, already knowing the European ones, becoming a professor at nineteen), was able to decipher hieroglyphics based on other language used in late Egyptian, Coptic, and he understood that he was faced with more types of hieroglyphs with different functions: he discovered the basis of the hieroglyphic writing system.

A subsequent discovery was decisive in its success in 1815 when two small obelisks were found on the island of Philae: a second stele with a double hieroglyphic and Greek text, and one with the name of another pharaoh, Ptolemy (Evergete II), with his consort Cleopatra VII. The scientist, reading the Greek text, had noticed that an oval ring called a cartouche was used eight times, containing numerous hieroglyphs together with two signs that are not read: a determinative one indicating the masculine or feminine category to which the name belongs and another indicating its ending. Champollion put the letters of Ptolemy's name in order, observing the position of the ideograms, under the corresponding signs of the cartouche, and was able to understand to each sign which reading of our alphabet they corresponded to. He did the same for Cleopatra, the other name pictured.

He, therefore, perceived that for each hieroglyph there did not necessarily correspond a word. He deduced that they were neither pictograms nor ideograms, as they did not represent exclusively objects or concepts, but within an identical text, they could have both symbolic and phonetic value. Champollion later transcribed an alphabet which he published in his book Le Lettre à M. Dacier thus laying the foundations for the birth of the science of modern Egyptology.

The Rosetta Stone, of which a faithful copy can be found walled up in the great hall on the ground floor of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, is still in the possession of the British Museum in London (see image on the left), despite repeated requests for restitution by the competent Egyptian authorities.

The arguments against its restitution are the same as those the British rely on for the Elgin Marbles. “It can give its best” in its current location, where it is seen in a very large historical context. Being the spearhead of the British Museum's Egyptian collection, if it were brought back to the Cairo Museum, which has less than half the number of British Museum visitors, it would be seen by fewer people.

Latest Articles

Admin

Seabourn Sojourn Cruise Stops in Safaga Port

The Seabourn Sojourn, the flagship vessel of Seabourn Cruise Line's ultra-luxury fleet, was built in 2008 at the T. Mariotti shipyard in Genoa, Italy. Measuring 198 metres, it can accommodate up to 450 guests in its 225 spacious all-suite staterooms.

Admin

Norwegian Sky Cruise Stops in Safaga Port

Norwegian Cruise Line operates a cruise ship called the Norwegian Sky. It was constructed in 1999 and can accommodate 2,004 passengers in addition to 878 crew members. The ship has several dining establishments, lounges and bars, a spa and fitness center, swimming pools, and a number of entertainment areas.

Admin

Explora II Cruise Stops in Safaga Port

Explora II, the second vessel in the Explora Journeys fleet, sets sail in 2024 to redefine luxury cruising. With 461 ocean-front suites, 9 culinary experiences, and 4 pools, this haven of sophistication and sustainability promises an unforgettable "Ocean State of Mind" journey to inspiring destinations.

Admin

Mein Schiff 6 Cruise Stops in Safaga Port

The Mein Schiff 6 is the latest cruise ship in the renowned TUI Cruises fleet, offering passengers a luxurious and sophisticated cruise experience. At 315 metres long, this floating resort features a range of dining options, entertainment, and recreational facilities, including a spa, fitness centre, and sports amenities.

Admin

Mein Schiff 4 Cruise Stops in Safaga Port

When the Mein Schiff 4 cruise ship docks in Safaga, Egypt, passengers are granted access to a realm of ancient wonders. Aboard this state-of-the-art vessel, guests can embark on meticulously curated shore excursions that showcase the region's most iconic landmarks, including the Giza Pyramids, the enigmatic Sphinx, and the remarkable tombs and temples of the Valley of the Kings in Luxor.

Admin

MS Europa Cruise Stops in Safaga Port

The Silver Moon, Silversea's latest flagship, is a luxury cruise ship that offers an exceptional travel experience for Venezuelans exploring Egypt. With a capacity of 596 guests and an impressive 40,700 gross tonnes, the Silver Moon maintains the small-ship intimacy and spacious all-suite accommodations that are the hallmarks of the Silversea brand.